Joya de Cerén Archaeological Park

The Joya de Cerén Archaeological Park

In the Shadow of Volcanoes: A Necessary Introduction to Archaeology in El Salvador

The Ancient Community of Joya de Cerén and its Setting

Discoveries at Joya de Cerén: Crops and Structures

Actions of FUNDAR and the Government at Joya de Cerén

The Round Table to Reach a Consensus on Conservation Measures for Joya de Cerén

Ground Surface Impermeabilization to Protect Structures in Area 2

Stabilization of Excavation Cuts

Archaeologist Specialized in Conservation

The Joya de Cerén Archaeological Park

In recognition of its importance, in 1993 Joya de Cerén was inscribed on UNESCO's List of World Heritage Sites. It is the only World Heritage Site in El Salvador.

This area originally formed part of the San Andrés hacienda, one of the larger landholdings in the Zapotitán Valley of western El Salvador. In the mid-twentieth century, the portion known as Joya de Cerén was sold to the government for an early experiment in agrarian reform. "Cerén" is a surname, while "Joya" is an archaic Spanish term still used in El Salvador to refer to a pocket or small valley with fertile soil amid hilly terrain.

Diverse versions have circulated concerning the discovery of this archaeological site. Fortunately, a key participant still works for the Salvadoran government and provided first-hand information in an interview conducted in 1989. The following narration is based on this and other information from verifiable sources.

In 1976, the government broke ground for a grain storage facility. The area was leveled by bulldozer, scraping off several meters (yards) of layered volcanic deposits in order to erect the facility on the firmer underlying soil. As this preparatory work neared completion, it exposed a site that had been entirely buried by 4 meters (13 feet) or more of these volcanic deposits, leaving no hint of its existence on the surface. The construction supervisor notified the Department of Archaeology of the Administración del Patrimonio Cultural (the government's cultural organ of the time).

Manuel López (then of the Department of Archaeology and currently with the Ministry of Foreign Relations) was sent to inspect the discovery. López recounts that he found that the grading work had already been completed at time of notification. The machinery had strewn numerous ceramic fragments across the area, including many examples of the well-known diagnostic of the Late Classic period (AD 600-900), Copador Polychrome. The construction crew told of small earthen structures that had been exposed - and destroyed. This was fortuitously verified by the fact that two structures remained visible, having been partially sectioned in one of the cuts along the property line. Each had a basal platform, and one showed a wattle-and-daub ("bahareque") wall. So it was evident to López that this was a Late Classic site with structures preserved under volcanic ash. He recorded it as Joya de Cerén. While the potential importance of this discovery was of course recognized, the destruction was done, the surrounding site area consisted of farm land with no other construction work on the horizon, and the Department of Archaeology was saturated with pressing projects at the time, operating with a dearth of human and material resources.

Two years later, in 1978, archaeologist Payson Sheets initiated the Protoclassic Project, whose principal activity consisted of a stratified random survey of 15% of the Zapotitán Valley. While thus engaged, project members were informed of the discovery of Joya de Cerén by an archaeologist working for the Department of Archaeology (Richard Crane). Sheets added the investigation of Joya de Cerén to the activities of the Protoclassic Project and supervised the beginning of excavation there in March, 1978, while project member Christian Zier continued the work from April through May of the same year. The two structures sectioned by the construction cut were partially excavated and the results firmly established the importance of Joya de Cerén: like Pompeii, the volcanic eruption "froze" a moment of time at this ancient Maya village. Structure 1 (with wattle-and-daub walls) was determined to be a house and in it were found tools and even toys. Structure 2 (later renamed as Structure 5) was an unwalled work platform. Both had roofs of grass thatching which had burned and collapsed as a thick layer during the eruption. Thatch samples were used for radiocarbon analysis, and together with results from later excavations (as evaluated by archaeologist Brian McKee) indicate a near-terminal date between AD 610 and 670 (calibrated, 2 sigma). Ridged agricultural fields nearly abutted the structures and the overlying volcanic ash preserved casts of maize plants.

A view of the first excavations at Joya de Cerén (1978) carried out by Payson Sheets and Christian Zier, in which the two structures sectioned by bulldozer were studied. To the left is Structure 1, a house (a person is in the doorway, and the large hole behind him was blasted in a wall during the eruption). On the right is Structure 2 (now renamed as Structure 5, here partially covered with plastic), an open platform which apparently served as a workplace. The only human remains found to date at this site consist of two burials. One burial was found beneath this platform but unfortunately had been mostly destroyed by the bulldozer. A path between the two structures was marked with a few stone slabs. This photograph shows how the tephra (ash and other airborne volcanic materials) accumulated in layers which piled against Structure 1 like a snow bank before covering it completely. These structures were built on a soil weakly developed from the white ash deposited from the Ilopango eruption (5th century AD), and about 30 centimeters of this ash may be observed in the cut beneath the house.

Later studies at Joya de Cerén have shown that the Ilopango ash also covered evidence of human activity predating these structures, so far represented only by a few scattered sherds of Late Preclassic pottery. Joya de Cerén also had a very late occupation. Just under the present ground level (at the top of this cut) are prehispanic remains probably dating to shortly before the Spanish conquest (in the Late Postclassic period, AD 1200-1524). These include a probable residential feature and the second human burial currently known at the site, both of which were impacted, ironically, during the use of a bulldozer to facilitate the excavation of the Classic period structures. This would be one of the only Pipil burials excavated to date. The Pipil were of Mexican origin and, by the eve of the conquest, dominated most of the western half of the territory of El Salvador (photo from the Joya de Cerén site museum).

In 1979-1980, Sheets surveyed parts of Joya de Cerén with remote sensing equipment, including ground penetrating radar and soil resistivity, in order to locate anomalies which could represent deeply buried structures. In this and subsequent studies, ground penetrating radar has proved particularly effective for locating possible structures, ridged agricultural fields, and for describing the pre-eruption topography of the site.

Excavations were resumed in 1989 and continued until 1996, during which time Sheets and his team excavated a total of 11 structures, and 6 more have been located but not excavated. Remote sensing suggests the existence of perhaps several dozen more.

In 1996, the cultural authorities (specifically, the Dirección Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural within CONCULTURA) imposed a moratorium on excavations at Joya de Cerén. The structures excavated up to that time were showing progressive deterioration and it was reasoned that no others should be exposed until a solution was found to ensure their preservation. It has been shown, however, that reburial is very effective in preserving excavated structures here. When FUNDAR assumed the co-administration of Joya de Cerén in 2005, the moratorium was lifted at our request and, in a meeting with the head of the Department of Archaeology, we invited Sheets to continue excavations at the site, offering to finance workers and to provide tools and other materials.

The limits of Joya de Cerén have yet to be firmly identified. It has been suggested that the site could measure some 5 hectares (12 acres) or more in extent; if so, only 2% or less of the site area has been excavated to date. Future investigations will undoubtedly yield many surprises in the 98% of the site as yet unknown.

In 1989, with the spectacular discovery of 3 structures by Sheets and his team, Ricardo Recinos became involved in supporting the excavations with unbridled enthusiasm, helping to support the project with donations ranging from buckets to tarps for protecting the delicate structures which were being excavated in the rainy season. The project had proposed to end with the construction of protective roofs over two structures and the opening of a site museum. As the final day approached, however, Sheets informed that he was going to rebury the structures. There were to be no roofs, no museum. Reburial was, without a doubt, the best option if the structures were not to be roofed.

Recinos sprung into action. As a board member of the Patronato Pro-Patrimonio Cultural (a now-defunct NGO), Recinos managed to convince his fellow directors to "adopt" Joya de Cerén, and with the end of the 1989 excavation season the Patronato installed the first protective roofs over the three exposed prehispanic structures. Starting with that action, the Patronato worked with the government to aquire land, install permanent roofs, open a site museum, and support several seasons of investigations led by Sheets. The Patronato's work culminated in 1993 with the inauguration of the Joya de Cerén Archaeological Park.

1993 also marked Joya de Cerén's inscription by UNESCO to the List of World Heritage.

The Patronato co-managed Joya de Cerén through 2004.

FUNDAR began its participation in the co-management of Joya de Cerén in mid-2004 under the Government's PTR program. At that time, the officials from CONCULTURA described Joya de Cerén as being in a state of "crass negligence". These conditions, and the improvements made by FUNDAR through December, 2009, are documented here under the section Park Improvements.

A storehouse with its walls fallen like a house of cards (Structure 7) and, in the background, a temascal or sweat lodge (Structure 9). Access to this area of Joya de Cerén was, for reasons unknown, formerly "restricted" (accessible only for VIP visits). FUNDAR opened it for public viewing in 2005.

Joya de Cerén is located in the fertile Zapotitán Valley (the arrow points at the site).

Joya de Cerén: A World Heritage Site

Joya de Cerén is a unique site in Mesoamerica by virtue of having been a living settlement that was covered by a sudden volcanic eruption. Its extraordinary importance merited the inclusion of Joya de Cerén in the List of World Heritage.

UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) maintains a catalogue of natural and/or cultural sites of outstanding importance which is called the List of World Heritage. Sites are nominated by state parties. UNESCO evaluates nominations in periodic meetings, applying strict criteria in order to decide if a site merits inscription to the list.

In 1992, CONCULTURA began the process of nominating Joya de Cerén as a World Heritage Site, charging its then employees Manuel López and Paul Amaroli with the tasks of completing forms and appending the necessary information. The nomination was accepted by UNESCO in 1993.

In your visit to Joya de Cerén, you will be accompanied by one of the park's three bilingual (Spanish - English) guides. They are identified by their yellow uniforms. From left to right: Archaeologist Karen Bruhns and guides María de los Ángeles Dimas Cruz, Carmen Mercedes Polanco Olivares and Roselia Duarte de Granados.

In the Shadow of Volcanoes: A Necessary Introduction to the Archaeology of El Salvador

Joya de Cerén is one of many instances known in El Salvador where volcanic eruptions have affected human activity in the past. This brief overview may prove useful in order to better appreciate the wider context of Joya de Cerén.

The territory of El Salvador is one of the most volcanic landscapes on Earth. The Isthmus of Central America was built by volcanic activity, and over the eons ash and other eruptive materials have weathered to form soils famed for their fertility.

This is, however, a living landscape. There have been many eruptions documented since the Spanish conquest (1524), and geological studies have identified numerous prehistoric events during the past several thousand years. Over the millennia, the human population living in the shadow of these volcanoes has had to cope, adapt, or perish. And sometimes, as with the enormous Ilopango eruption (5th century AD) which severely affected about 3,000 square kilometers (1,200 square miles), any desperate effort to survive would have been futile for the many thousands who were engulfed by such catastrophic events.

Lake Ilopango is located in central El Salvador. Several eruptions have originated from beneath its waters. The last one was only yesterday in geological terms, lasting from December, 1879 to January, 1880, and was fortunately a minor event. The huge 5th century AD eruption was a human and ecological disaster that affected about 3,000 square kilometers (1,200 square miles). The hallmark of this eruption is its distinctive white and finely textured ash, known as "tierra blanca", and distinguished in geological and archaeological studies as "Tierra Blanca Joven" or TBJ for short.

The topic of ancient humans and volcanic eruptions has been a constant in Salvadoran archaeology since its formal inception in the early 20th century. In 1917, Jorge Lardé discovered a cultural stratum exposed by a road cut in flank of Cerro El Zapote (a hill located in the southern part of the capital city). The stratum had been buried under the white ash of a then unknown eruption (it was later recognized as TBJ from Ilopango). Together with Archaeologist Samuel Lothrop, Lardé continued his investigation of this discovery in 1926. At the San Andrés site, excavations between 1940-1941 conducted by John Dimick revealed an almost superficial layer of tuff (consolidated volcanic ash) which had fallen on the structures some time after the site's abandonment (this deposit is called San Andrés Tuff or "Toba San Andrés"), while in his deepest excavations he found a layer of white volcanic ash covering a cultural stratum, just as Lardé had noted years before. It was during the same decade of the 1940s that Archaeologist Stanley Boggs found a similar situation in the early construction stages at the Tazumal site.

In the course of salvage excavations prior to construction of the Cerrón Grande reservoir (1974-1976, with Boggs as general director), two notable discoveries were made beneath the TBJ ash of Ilopango: a circular pyramid, and an agricultural field marked by ridges and furrows. Since that time over 20 similar fields have been found covered by TBJ in the area of San Salvador, the Zapotitán Valley and Chalchuapa. It is suspected that they were for maize, though no direct evidence of this has yet been found.

Construction for a new roads and subdivisions has exposed many ancient agricultural fields with ridges and furrows which were covered by the white TBJ volcanic ash from the Ilopango eruption. Here Sonia González provides scale at a field exposed during the widening of the Calle a Huizucar in southern San Salvador. The soil of this field is dark brown. Note the modern corn field above.

A tragedy for Salvadoran archaeology was the 1984 destruction of an entire settlement that had been buried under the Ilopango TBJ ash. It was apparently the equivalent of another Joya de Cerén, but about two centuries older. This site was exposed and destroyed by bulldozers grading for the La Cima subdivision in southwestern San Salvador.

In the 1990s, construction work in the municipality of Antiguo Cuscatlán exposed maize fields of considerably greater antiquity than those under TBJ ash. Studies indicate they were buried by a relatively minor eruption around 800 BC. These rank amongst the earliest preserved agricultural fields in Mesoamerica.

One of the ancient maize fields exposed by construction in the jurisdiction of Antiguo Cuscatlán. This field was on a strongly reddish-brown soil, and casts of maize plants were found on its surface. Radiocarbon analyses indicate a date of about 800 BC for this field. It was covered by layers of dark gray volcanic ash erupted from the nearby crater of Plan de la Laguna (now the location of several factories). As the level string shows, this field has a moderate decline towards the left (north). The yellow tape measure is extended to one meter. Rows in present-day corn fields are planted about a pace apart, and this appears to have been the practice since nearly 3,000 years ago.

Colonial features have also been studied which were buried by the 1658 eruption of the small El Playón Volcano situated at the eastern end of the Zapotitán Valley. In addition to ash, this eruption spewed lava which flowed about 8 kilometers (5 miles) northward, forcing the Pipil town of Nejapa to be abandoned. The ash fall choked the Sucio River, which as the valley's main drainage quickly led to the formation of a temporary lake (the small body of water known as the Laguna de Zapotitán, which was drained in the 20th century, may have been a remnant of this event). After several days the accumulated water broke through the ash, causing a raging flash flood (lahar) downstream that deposited a thick layer of volcanic mud. In 1995, while carrying out test excavations in preparation for the new museum at San Andrés, Paul Amaroli discovered an indigo processing facility ("obraje de añil") which had been covered by over 4 meters (yards) of this volcanic mud.

The ancient community of Joya de Cerén was buried by an otherwise inconsequential eruption that has been studied by Dan Miller and other geologists. The "Loma Caldera" eruption took place between approximately AD 610-670 and apparently issued forth from a vent located about 600 meters north of Joya de Cerén. The tephra (airborne materials) ranged from fine ash to gravelly "lapilli", with intermittent large volcanic bombs. In a relatively short time (judged to be as little as a few hours, or at most a few days), several layers of these materials covered the site, totaling about 4 to 8 meters (13-26 feet) in thickness. The tephra from the Loma Caldera eruption only reached about 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) from its source.

Visitors to Joya de Cerén often ask if any victims of the eruption have been found in the excavations. Small victims have been discovered: the three storehouses studied to date contained the remains of a few mice and of a duck (whose remains are displayed in the site museum). Weevils were found with stored maize and beans. Several small birds have also been found in outdoor areas, killed in flight (or while perched) as often ocurrs during volcanic eruptions. But human victims have yet to be found. In Miller's evaluation, this eruption began with a series of earthquakes and direct evidence from the site shows their effects at the very onset of this event (part of the cornice of Structure 3 broke off and fell on a ground surface where only a tiny amount of tephra had accumulated). It is likely that with earthquakes and the onset of tephra fall, the denizens of Joya de Cerén lost no time in evacuating the area. Whether or not they were able to flee beyond the lethal area of the eruption is something that only future investigations can resolve.

The

Ancient Community of Joya de Cerén and its Setting

Several scholars agree that from the Middle Preclassic period (900-500 BC) on, the territories of western El Salvador and adjacent southern Guatemala constituted an important Maya subregion. The Maya stelae bearing the oldest Long Count dates currently known have been found in this area, and by the Late Preclassic (500 BC - AD 250), the region hosted several important centers which were probably the capitals of early kingdoms, such as Takalik Abaj, Monte Alto, Chocolá and, exceptional for both its size and complexity, the huge site of Kaminaljuyú. On the basis of iconography and epigraphy, Federico Fahsen has proposed that the inhabitants of this subregion may have been ancestral to the Maya ethnolinguistic group called Cholan.

In western El Salvador, these early Maya are represented at several sites, foremost of which is the Chalchuapa archaeological zone. Archaeological studies have shown that Chalchuapa is one of the most ancient continuously occupied communities known (and is possibly the most ancient of all), reaching back without interruptions to 1200 BC, and perhaps as far as 3000 BC. By the Late Preclassic a large center had emerged, known as El Trapiche/Casa Blanca, with evidence of warfare (over 30 victims of sacrifice found in a single context) and an early Maya stela. Many other contemporaneous settlements existed in the western half of Salvadoran territory, but life was interrupted - or terminated - with the gigantic Ilopango eruption in the 5th century AD. The eruption deposited huge quantities of fine white ash (called "tierra blanca joven" or TBJ), reaching about 50 meters (160 feet) in thickness next to its source (Lake Ilopango), and up to roughly 20 meters (65 feet) in the area of San Salvador. Even as far as Chalchuapa, 75 kilometers (about 45 miles) from the source, about 50 centimeters (20 inches) of TBJ fell. Archaeological investigations show that the inhabitants of Chalchuapa endured this major inconvenience, but much of western El Salvador was left, in the words of Archaeologist Stanley Boggs, "like a white desert". The Ilopango eruption ranks as one of the world's largest volcanic events in the past 10,000 years.

This was the case of the Zapotitán Valley, where Joya de Cerén and San Andrés are located. This is one of the major valleys of El Salvador, renowned for its fertile soils (which sadly are now being covered with subdivisions and factories). After a century or so, the sterile TBJ had weathered sufficiently to sustain agriculture, and a wave of recolonization spread from places like Chalchuapa that had survived the disaster. It was then (around AD 500-550) that some 200 or 300 Maya communities were established in the Zapotitán Valley, including Joya de Cerén and San Andrés. It is interesting to note that vestiges of pre-Ilopango settlements have been found beneath both of these sites.

While San Andrés grew to become a regional capital with an extension of over 2 square kilometers (0.8 square miles), Joya de Cerén was, during its brief existence, a relatively small community and possibly tributary to San Andrés. The total area of Joya de Cerén has yet to be accurately determined.

Archaeology at Joya de Cerén is often compared to that of Pompeii, where a sudden volcanic eruption "froze" a moment of time which we can study in exceptionally rich detail. This is also the case at Joya de Cerén, where volcanic tephra covered houses and other structures as well as surrounding farmland, preserving them to a degree unparalleled in Mesoamerica. Perishable materials, such as seeds, wooden artifacts, basketry, and recipients made of tree gourds may here be studied as casts (which can be filled with dental plaster) or as carbonized but complete specimens. In some rare hermetically sealed circumstances, objects (such as cacao seeds in Structure 4) have actually been found preserved intact. The information gleaned from Joya de Cerén has been revolutionary in understanding the daily life of the ancient Maya.

Discoveries

at Joya de Cerén: Crops and Structures

Excavations at Joya de Cerén have discovered 11 structures and a variety of crops.

Crops

Several different cultigens have been identified at Joya de Cerén and have proved of great importance in understanding the complexity of ancient Maya agriculture as practiced at a relatively small settlement. Agriculture was intensive in the areas studied so far, with the cultivated landscape virtually touching upon the structures.

To date, the most abundant cultigens found growing in fields are maize (Zea mays of teh Nal-Tel/Chapalote variety) and manioc (Manihot esculenta). In addition, either farmed or stored, the following crops have been identified:

- Squash (local name "ayote", Cucurbita moschata)

- Beans (local name "frijoles", Phaseolus vulgaris and Phaseolus lunatus)

- Chile (Capsicum annuum)

- Malanga (local name "quequexque", Xanthosoma violaceum)

- Cotton (local name "algodón", Gossypium hirsutum)

- Agave (local names "maguey" and "henequén", Agave spp.)

- Achiote (local name "achote", Bixa orellana)

- Jocote or hog plum (local name "jocote", Spondias spp., probably Spondias purpurea)

- Cacao (Theobroma cacao)

- Guava (local name "guayaba", Psidium spp.)

Structures

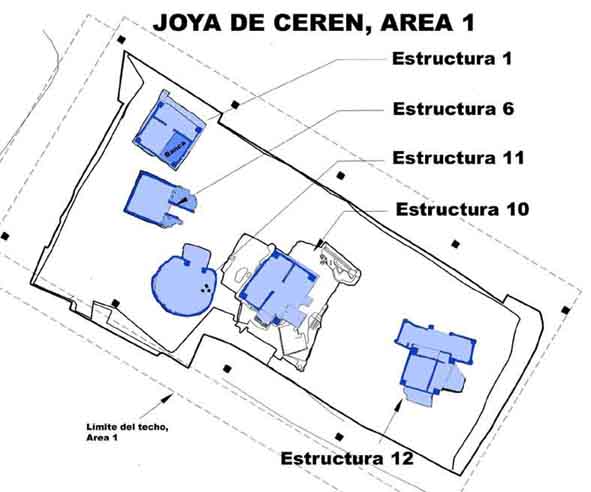

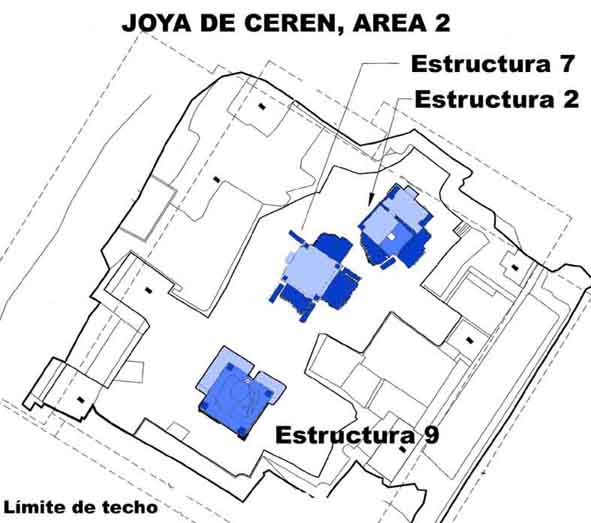

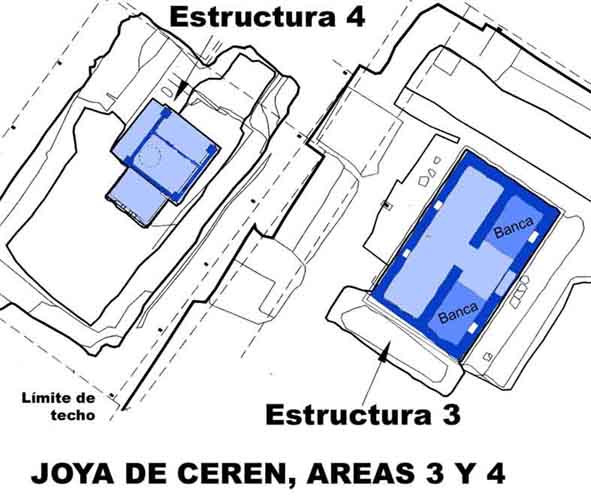

A total of 11 structures have been partially or completely excavated. Structure numbers are assigned according to the order of their discovery. There are 4 areas of excavation, or "operations", at Joya de Cerén, which have also been referred to as "groups", which tends to confuse visitors since two "groups" (3 and 4) have only one structure each. Because of this, we have used the term "area" for the purposes of interpretation.

Plan of Area 1 (adapted from the Joya de Cerén management plan).

Plan of Area 2 (adapted from the Joya de Cerén management plan).

Plan of Areas 3 and 4 (with Structures 3 and 4; adapted from the Joya de Cerén management plan).

Below are short descriptions of most of the visible structures at Joya de Cerén. All of the structures were built of earth. Contrary to expectations about earthen architecture, the construction material used was not exceptionally clay-rich. Roofs were of grass thatching supported on light wood frames.

Structure 1 (Area 1)

This was the house left sectioned by a construction cut in 1976 which provided the first evidence for the existence and importance of Joya de Cerén.

|

|

Structure 1, a house. |

|

Structure 1 is in relatively poor condition. In 1976 most of its porch was cut away by a bulldozer. After its partial excavation in 1978, a modest tin roofed shelter provided some protection from the rain, but by 1986 both the shelter and the excavation cut had collapsed, breaking off the two front columns and the wattle-and-daub wall directly behind them. The other three walls were found during the large scale excavation of the site beginning in 1989. They had detached from the columns and fallen on the ancient surface in graphic testimony of the violence of the eruption. The fallen walls were unfortunately destroyed by the excavators in order to examine the areas beneath them. More damage occurred when this structure was subjected to an ill-advised experiment. Scalding-hot sand was piled against the basal platform in an effort to quickly dry it out; this caused generalized detachments of its surface, leading to its present somewhat battered appearance.

Like most of the other known buildings at the site, Structure 1 consists of a basal platform with solid columns in each corner, and wattle-and-daub walls running between the columns. It had a tiny porch in front, with a door leading to its sole room, half of which was occupied by a solid earth "bench" which (when covered with mats) would have served as a bed. The basal platform, columns and bench were hand modeled from moist earth - basically mud - and in at least one fractured portion hand marks were visible left from the shaping process. In present-day traditional houses (now very scarce), the purpose of basal platforms is to elevate the floor level above the reach of moisture which can be a problem during the rainy season.

It has been proposed that the typical household at Joya de Cerén is represented by Structures 1 (a house, whose small size practically limited its use to sleeping), 6 (a storehouse), and 11 (a kitchen). While this may be a valid interpretation, to date it is the only example known of this proposed domestic group.

In other contemporary sites, human burials have been found beneath and adjacent to houses. These individuals were probably family members who were once occupants of the houses. Although this is expected to be the case at Joya de Cerén, the only excavation to date beneath a building was at Structure 5 (sectioned by a bulldozer), where part of a human burial was in fact present.

Structure 2 (Area 2)

This is the second of the two houses known at the site and is very similar to Structure 1, although much better preserved. Its bench (bed) has a niche where two bowls had been stored, one inverted over the other. The interior of one of the bowls had a thin layer of food remains, which still showed streak marks from fingers used to scoop up a last meal.

|

|

Left: Structure 2, with its porch on the left and its bench (and its niche) on the right. Right: The door of Structure 2 is still full of volcanic tephra. |

|

Structure 3 (Area 3)

This is the largest structure presently known at Joya de Cerén, and it is thought that nearby Structure 13 (still unexcavated) is very similar; they (and possibly additional structures) may form a plazuela group. Structure 3 was erected on a massive basal platform and has thick walls of modeled earth. It has a rectangular floor plan with a single doorway centered on one of its long sides. Its interior is divided in two rooms, with two benches in the first, and niches and both rooms. Here, as in other structures, broken handles salvaged from ceramic pots were affixed to the walls in positions where they would have been useful for tying doors (such as a sheet of cloth or cane bound with string), while others placed in the corners may have been useful for hanging objects. The roof burned and collapsed during the eruption and, when uncovered by excavation, it formed an impressively thick layer of carbonized grass thatch in both rooms. The roof was supported on several long posts located outside of the structure, and these were found thrown to the ground and carbonized.

Structure 3.

Left: This side of the structure was largely destroyed by a backhoe employed by Payson Sheets in his 1989 excavations. The gouged wall may be noted.

Right: A view

of the 1989 excavation by Payson Sheets. This backhoe caused severe damage

to Structure 3 (the damaged portion is covered in plastic). Sheets (wearing

a dark shirt) appears above the cut on the right.

This structure was found nearly empty. A large pot was found on one of the benches and a bowl had been perched on top of a wall. The sharp edges of the exterior corners of the walls and basal platform gave the impression that this structure had recently been finished when the eruption struck. Its exterior walls are marked with undulating bands left by contact with the layers of volcanic material.

The excavators of Structure 3, Andrea Gerstle and Payson Sheets, have suggested that it functioned as a civic structure perhaps used by village elders and their guests. We would suggest another possibility. Structure 3 fully (if modestly) adheres to the canons of elite residential architecture as found at contemporaneous Maya sites such as Copán, both in its general layout and in details such as niches, hangers, and large benches. Indeed, in this regard the only salient exceptional trait of Structure 3 is that it was built of earth, rather than earth, stone, and lime plaster. So it is possible that Structures 3 and 13 may constitute an elite residential compound.

Structure 6 (Area 1)

Structure 6 is relatively simple. It does not have a basal platform. Only a single wall, that with the doorway, was of wattle-and-daub (bahareque), while the other three walls were of cane with some mud slathered over their bases. The structure contained several ceramic vessels, a mano and metate, so-called "doughnut stones", and obsidian tools. Some vessels were in use to store grain. The charred remains of a duck were also found, as well as the skeletons of mice. Structure 6 is one of three storehouses known at Joya de Cerén.

Structure 6 (a storehouse) and, in the background, Structure 11 (a circular kitchen). The depression in the corner of Structure 6 is a crater left by the impact of a volcanic bomb during the eruption that buried Joya de Cerén.

Structure 9 (Area 2)

Sweat houses once formed part of households throughout Mesoamerica and continue to be important for many Maya living in Guatemala and southern Mexico. In Mesoamerican archaeology, these structures are usually referred to with the term temascal, which is derived from the Nahuatl word temazcalli. This type of building is called tuj by the modern K'iché, Kaqchikel and Tz'utujil Maya of Guatemala, where it is used for bathing, childbirth, and curing. Remains of temascals have been found in many archaeological sites, with the notable discovery of eight at Piedras Negras in northern Guatemala. One of the first archaeological examples ever excavated was discovered by Antonio Sol in his 1929 excavations at Cihuatán, El Salvador. But the temascal at Joya de Cerén (Structure 9) is by far the best preserved of all. Like other temascals, Structure 9 has a low entrance, through which the users entered crawling, in order to keep heat inside. Its interior, which has only been partially excavated, has a fire box made of river cobbles and earth mortar, surrounded by benches surfaced with pieces of thin stone slabs. A small hole in the ceiling helped for ventilation.

The temascal (Structure 9). During the eruption, its dome-shaped roof was impacted by a volcanic bomb which left the large hole visible here, and as the eruption progressed, the roof fractured and sunk slightly under the weight of accumulated volcanic material. The ventilation hole appears on the roof above the low doorway.

The temascal's roof was a major surprise: it is a dome, made of wattle-and-daub, and originally protected from the rain under a thatched shelter. It is the only dome yet known in Mesoamerican architecture. The temascal has a basal platform and thick walls of modeled earth.

Structure 11 (Area 1)

This kitchen is circular and had walls of widely spaced cane which would have helped ventilate its smoky interior. Within are the three stones of the Mesoamerican hearth (nearly extinct in El Salvador - in Nahuizalco the Náhuat-derived term for these stones, "los tenamashtes", still survives). When it was excavated, Structure 11 was found to contain a wooden shelf, several ceramic vessels for cooking and serving food, "yaguales" (circles of twisted grass used to support round-bottomed vessels), a metate, painted bowls made of tree gourds (jícaras de morro), and several other artifacts.

Structure 11 (a kitchen) surrounded by the ridges of a corn field. The three hearth stones may be seen to the rear.

In the vernacular thatched architecture of El Salvador (nearly extinct), kitchens were built at a short distance from houses. Kitchen fires were fairly common, especially during strong winds, and the separation helped ensure that the flames did not reach any dwellings.

Structure 12 (Area 1)

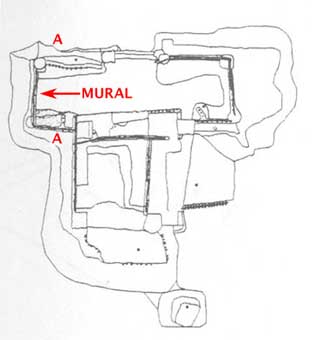

This is a unique structure. As in the two known houses, it has a basal platform with corner columns, but the similarities end there. It has a long porch with six niches, a lattice window, and remains of a modest mural in its interior (representing red flowers or stars?). The structure has two rooms, one small with a lattice window, and the other smaller yet. Access to the larger room was notably labyrinthine. The principal investigator of the site has proposed that Structure 12 may have been the workplace of a female shaman.

The mural in Structure 12 is the only one known in the prehispanic architecture of El Salvador. As we illustrate below, the mural was not identified by the site's excavator and is now in very poor condition due to ill-advised actions and lack of conservation.

The enigmatic Structure 12. The lattice window of its porch is visible to the right.

Structure 12 originally had lattice windows in its porch and in the larger of its two rooms. This photo (taken in 1991) shows the room's window before its destruction in the 2001 earthquake. The earthquake had a magnitude of 7.7 and caused the upper part of this wall to collapse.

Structure 12 during its documentation in 1996 by Manuel Murcia and Paul Amaroli for a conditions evaluation report prepared for CONCULTURA. Murcia stands in front of the mural on the eastern wall of the porch. Murcia was in charge of Joya de Cerén during several years and contributed in many ways to Salvadoran archaeology. He identified the mural in 1991, which curiously had not been noted during the structure's excavation. It was described for the first time in the 1996 report.

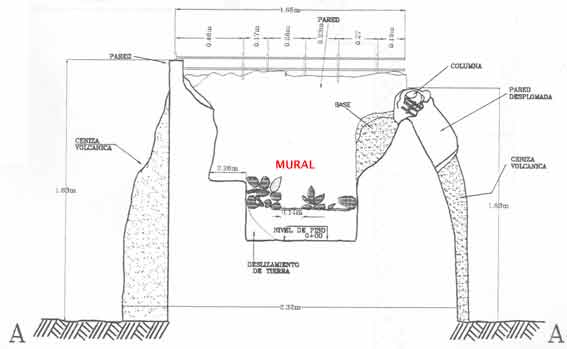

ABOVE: Location of the mural in a floor plan of Structure 12.

BELOW: The section A-A shown in the floor plan. The mural consists of red paint applied on a light background. Here the red color is represented by grey shading. Drawings from the report of Murcia and Amaroli.

ABOVE: Photo taken in 1991. The arrow indicates the portion of the mural exposed at that time.

BELOW: Detail of the same view from 1991. As can be seen, the mural was in relatively good condition. Most of it was still covered by tephra.

ABOVE: The same view in 1996 (the detail shown in the previous photo is to the left). Several things happened to the mural between 1991 and 1996. It was completely exposed, cracks were caulked and new plaster was applied to some areas. The mural has lost the brilliance visible in the 1991 photo. The wall's dark tone is due to its moist condition. From approximately 1994 through 2005 the structures at Joya de Cerén were sprayed with water several times a week. It is most regrettable that the mural was not recorded immediately following its excavation when its details were much more evident, and that timely conservation measures were never implemented.

ABAJO: The same view in 2009. The mural is nearly invisible (here it is framed by a red rectangle). More changes are visible: the floor has been filled up to the base of the mural, including scraps of plastic and black geotextile. The former practice of spraying the structures with water (suspended by FUNDAR) caused the fragmentation and loss of the wall surface - including part of the mural - at the juncture with the fill.

Detail photographed in 2009 of the leftmost part of the mural after it was carefully moistened by Archaeologist Claudia Ramírez. This helps make visible the remaining red pigment. The lower portion has largely crumbled away due to the former practice of spraying the structures with water. Ramírez is studying pigments and their conservation on Joya de Cerén's structures.

Actions of FUNDAR and the Government at Joya de Cerén

In 2005, FUNDAR began its collaboration with the Government in the management of the Joya de Cerén Archaeological Park. As described by government authorities, the park was then in a state of "crass negligence". Between 2005 and 2009 (when FUNDAR decided to end its participation in park management), several actions have been carried out which have had a positive impact at the park, including:

- Improvements in the conservation of the ancient structures.

- Extensive repairs to damaged roofs which protect the archaeological structures.

- Construction of new roofs for protection of the structures.

- Zonification of use of the park, improving the security of the archaeological areas.

- Greatly extending the archaeological trail, including an area previously closed to visitors.

- Planting of extensive gardens to improve the appearance of the park.

- Conversion of a major portion of the trail from a paved road to an attractive path.

- Creation of a parking area.

- Creation of a picnic area.

- New signage.

- Remodeling of the site museum.

- Installation of a water distribution system throughout the park for the gardens, and repairs to pumps and cisterns.

These actions are described below with photographs, when possible using "before and after" views.

Upon beginning our involvement at Joya de Cerén in 2005, we found the following situations regarding conservation of the archaeological structures:

- The structures were constantly being modified with new plaster and minor reconstructions. These procedures resulted in irreversible changes affecting the authenticity of the structures.

- The structures were being sprayed with water on a daily basis using a water hose or backpack sprayers. This caused constant cycles of wetting and drying in the structures, leading to generalized cracking and progressive loss of their surfaces, particularly evident in those areas in contact with tephra which acts as a sponge to retain moisture.

- The water applied with sprayers sometimes had an infusion of sap from the escobilla plant (Sida acuta), with the rational that this sticky substance aids in consolidating the structures. Two laboratory studies (one by the Smithsonian Institute and the other by the Getty Conservation Institute) have shown that the infusion (in the concentration used at Joya de Cerén) had no consolidating properties whatsoever.

- The structures were sweep daily with brooms made of stiff straw, resulting in unnecessary superficial erosion.

|

|

The former practice of spraying the fragile earth structures with water is shown in this photograph from May, 2005 (Structure 3). |

Structure 3 with its base and surrounding ground surface saturated with water. One study undertaken at the site attributed the moisture to capillary movement from the water table. In reality, soil studies here have shown that the water table is much too deep for this to happen. The actual cause was the practice of wetting down the structures and, to a lesser degree, the penetration of rain water. |

|

| The temascal (Structure 9) after having been sprayed with water, leaving its base literally dripping. This photograph was taken in March, one of the driest months of the year. The practice of wetting the ancient structures had been in effect for over a decade when CONCULTURA ordered its suspension acting on recommendations by FUNDAR. |

|

| One of many examples of a structure with surface degradation and loss. The former practice of wetting the structures was the main cause of this damage. |

The Round Table to Reach a Consensus on Conservation Measures for Joya de Cerén

In May, 2005, it was agreed to suspend any direct contact with the ancient structures, including the practices of spraying with water, sweeping, and restorations. A meeting of experts was planned in order to reach a consensus on the routine conservation measures recommended for Joya de Cerén, which had never been defined.

This workshop was organized by CONCULTURA and FUNDAR, and was called the Round Table to Reach a Consensus on Conservation Measures for Joya de Cerén. Several sessions were held at the site and at the National Museum of Anthropology. The participants included experts in the conservation of earth structures and those government officials responsible for the administration of Joya de Cerén:

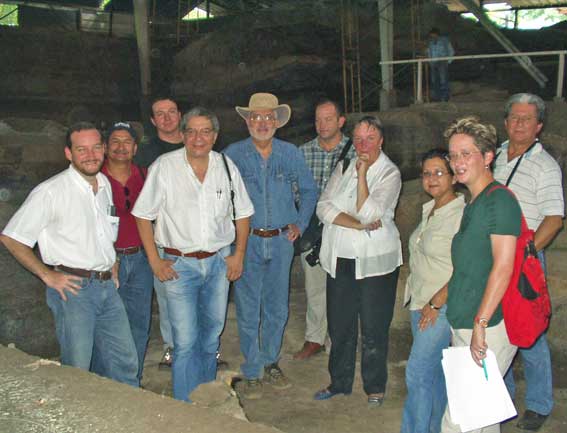

NAME Federico Hernández President of CONCULTURA Héctor Ismael Sermeño National Director of Cultural Heritage, CONCULTURA Gregorio Bello Suazo Archaeologist, Director of the National Museum of Anthropology, CONCULTURA Irma Flores Architect with a MA in conservation, Coordinator of Historic Zones and Sites, CONCULTURA Fabricio Valdivieso Archaeologist, Head of the Departament of Archaeology, CONCULTURA Fabio Amador Archaeologist, National University of El Salvador, founding member of FUNDAR Víctor Sandoval Restoration Architect, Guatemala Enrique Melara Civil Engineer, specialist in soils Françoise Descamps Architect, expert in conservation, Getty Conservation Institute Carolina Castellanos Expert in conservation, Getty Conservation Institute Rodrigo Brito President of FUNDAR Paul Amaroli Archaeologist, FUNDAR

The participants in the Round Table to Reach a Consensus on Conservation Measures for Joya de Cerén (2005). From left to right: Federico Hernández, Enrique Melara, Fabricio Valdivieso, Gregorio Bello Suazo, Rodrigo Brito, Fabio Amador, Françoise Descamps, Irma Flores, Carolina Castellanos, and Víctor Sandoval. Other participants absent in the photo: Héctor Ismael Sermeño and Paul Amaroli.

The meeting recognized that it is not possible to predetermine all the actions necessary or appropriate for conservation at this site because these depend on many variables, on funding, on advances in the field of conservation, and many other factors. On finalizing the meeting, however, several routine conservation measures were agreed upon which are considered applicable to Joya de Cerén. Click here to read the consensus (PDF document in Spanish, 30kb).

The consensus supports the permanent suspension of those practices recognized as negative, including wetting and sweeping the structures, and carrying out unnecessary reconstructions, including so called "sacrifice" plasters which, as they flake away, also carry off original portions of the structures.

Most of the measures agreed upon have been put into effect: environmental monitoring, repair of leaking roofs, construction of new roofs, and sealing off areas with wire mesh to keep animals out of the structures (these conservation measures are described below under Park Improvements). A pending measure of great importance is the acquisition of land surrounding the present archaeological park.

|

|

| Environmental monitoring. Six HOBO sensors have been installed which record temperature and relative humidity every hour. | |

Impermeabilization to Protect the Structures in Area 2

The structures in Area 2, including the temascal (Structure 9), were very affected by moisture. This was generally due to the same practice of spraying with water. But during the rainy season, this area had a much more severe problem to the extent that water actually flowed across the surface.

|

|

Extreme Moisture Problems in Area 2 The temascal and other structures in this area would become exceptionally saturated with water during the rainy season, and at times water would flow over the ancient ground level (here covered with a thin protective layer of a few inches of imported white volcanic ash ("tierra blanca"). When we inspected this situation during rainstorms, we found that water was seeping forth from the excavations cuts. We concluded that the rain water falling on the surface outside of the protective roof was penetrating through the tephra until reaching one of its dense layers, and then the water flowed almost horizontally on top of the layer, following its gentle downslope towards the west until pouring out at the excavation cuts. |

|

The foregoing indicated a possible solution: impermeabilizing the ground surface east of Area 2.

Using black plastic sheets, we covered approximately 450 square meters (about 4,800 square feet) of the surface east of Area 2. Then we covered the plastic with a layer of earth and planted ground cover to for stabilization and to make it more attractive. Thus protected from the Sun, this plastic will last for years to come. Water no longer pours from the excavation cuts, and although the humidity increases seasonally, it is a much more manageable situation. This impermeabilization requires maintenance of its ground cover to hold the soil over the sheeting.

|

|

Impermeabilization to Protect Area 2 Clockwise from above: Emplacement of plastic sheeting and earth; the stabilizing ground cover; and the present appearance of the impermeabilized area. The rain falling on this area flows into drainage channels. The gentlemen in the photographs are Rafael Amaya (Park Administrator, FUNDAR) and Antonio Menjivar (Head of Joya de Cerén, CONCULTURA). |

|

Stabilization of an Excavation Cut

We found a collapsing excavation cut located just east of Structure 3. It was located outside of the protective roofs, and had been severely eroded after many years of tropical rainy seasons. A notable collapse took place during the heavy rains of October, 2005. FUNDAR stabilized this cut for the protection of the archaeological site.

|

BEFORE The collapse. This was originally a straight and vertical cut, but it was very eroded after over a decade of exposure to the weather. The prolonged rains in October, 2005, lead to a notable collapse. |

|

In order to stabilize this cut, first we built a retaining wall and compacted earth behind it. |

|

Parting from the retaining wall, we created a sloped surface of compacted earth, made with a stable inclination of 45 degrees. |

|

We then planted ground cover to minimize erosion of this new surface. |

|

NOW The stabilized cut.. |

Archaeologist Specialized in Conservation

Archaeologist Claudia Ramírez (Department of Archaeology, CONCULTURA) has specialized in the conservation of earth architecture, with emphasis in Joya de Cerén. She is conducting studies concerning this site's structures, including condition assessments and conservation procedures.

Elimination of Hazardous Vertical Cuts in Tephra

One of the first recommendations made many years ago for the conservation of Joya de Cerén was to reduce or eliminate the tall vertical (or nearly vertical) excavation cuts which were left next to some of the structures, and Structure 4 was singled out as being at greatest risk. The vertical cuts made in the unstable tephra could collapse at any time, and especially so during any of the earthquakes which are common in this part of the world. Soils specialist Enrique Melara was the first to raise the alarm about this risk to Joya de Cerén in his report distributed in 2001, but years went by with no response. A limiting factor was the fact that Structure 4 was covered by a poorly built provisional roof which was itself a hazard. This roof was supported right next to the vertical cuts.

In 2008, the provisional roof over Structure 4 was replaced with a much larger permanent roof which is now joined with the adjacent roof over Structure 3. At the beginning of 2009, FUNDAR submitted a proposal to CONCULTURA for the reduction and elimination of the vertical cuts surrounding Structure 4. We proposed to completely eliminate the thick "wall" of tephra separating Structures 3 and 4. This "wall" nearly touched Structure 4 and its elimination would reduce the risk to both structures and allow their joint visualization by visitors. A general opinion exists that this would also improve the environmental conditions for Structure 4. The vertical excavation cuts surrounding the other three sides of Structure 4 would be reduced to a more stable slope of about 45 degrees. According to our proposal, the Department of Archaeology would supervise workers hired by FUNDAR. Work was begun in May, 2009, with 7 workers provided by FUNDAR under the supervision of Claudia Ramírez and later Liuba Morán, both of whom are Archaeologists with the Department of Archaeology.

Update: this important conservation work was suspended in January, 2010, by the first administration of the Secretaría de Cultura. After a lapse of many months, the work was resumed under the new administration of Secretary of Cultura Dr. Héctor Samour, and presently (December, 2010) the work continues.

Profile from west (left) to east showing the excavation cuts next to Structures 3 and 4. The potential collapse of these vertical cuts represents a grave hazard for these prehispanic structures, especially number 4. The ancient ground surface has a marked downslope between Structures 3 and 4.

In this view from 2005, Structure 4 is shown surrounded by unstable vertical cuts of tephra, just as they were left by the archaeological excavations conducted over a decade ago. The cuts reach over 6 meters in height and even a partial collapse could drop tons of tephra on this fragile structure. Structure 3 is towards the right (east), on the other side of the large "wall" of tephra which almost touches Structure 4. The points of light on the floor of the excavation are from the numerous holes which then existed in the roof over this area, through which rainwater also flowed to the detriment of the ancient structure.

A view similar to the previous photo, taken in the second half of 2009. . Several people are excavating the "wall" of tephra separating Structures 3 and 4. Here Structure 4 has been sheltered to avoid any damage during the work.

Photograph taken on the "wall" of tephra mentioned above.

Protecting the ancient structures from animals

While the archaeological structures have been covered by four shelters for many years, none of these roofs had its sides enclosed to prevent the entrance of animals which damage the ancient features. These include:

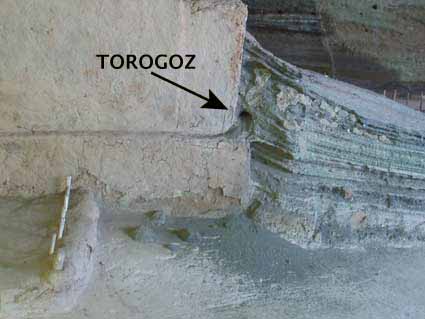

- Birds. In general, their droppings foul the structures. Before the practice was suspended by FUNDAR in 2005, in the past the structures were periodically "cleaned" by scraping the droppings off with metal spatulas, which also scraped away part of the structures themselves. Some birds, particularly the torogoz (El Salvador's national bird), excavate their nests in vertical cuts of loose tephra which can cause damage to the structures.

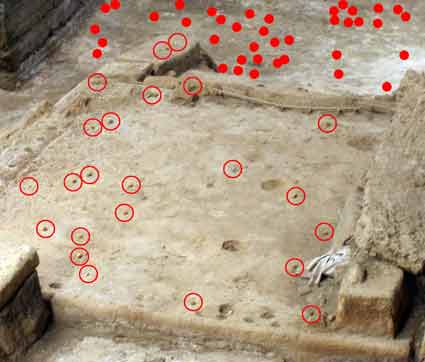

- Bats. They also deposit guano on the structures. While hanging from the roofs, they feed on fruit and drop the seeds which can impact and damage delicate surfaces of the structures.

- Foxes. Foxes are relatively common in this area. They are prone to digging and have caused notable damage to the structures. Raccoons and rabbits cause similar damage and have also been noted in the vicinity of the ancient structures.

Despite the fact that damage caused by animals was recognized as a major conservation problem since about 1990, no measures were ever taken to prevent them. When FUNDAR began its participation in the management of Joya de Cerén, we proposed to completely enclose Area 1 (the largest of the four areas) with lateral structures which would have sealed it off from light and insects (certain insects are also a problem at the site, as they nest by excavating small holes or constructing mud nests which adhere to the ancient structures). We believed that this would have been an optimal solution. The absence of light would prevent the growth of problematic algae, moss and other green plants. Lights would be turned on only while entering with groups of visitors. The guides could have illuminated successive structures in order to discuss each one, and with appropriate lighting this would have been a dramatic experience. Ventilators located high on the roof could help regulate the temperature, as could a thermal coat on the roof itself. Sadly, due to several reasons (mostly funding), it was not feasible to implement this concept at the time.

In 2006, we installed lights over the ancient structures to keep bats from roosting. The lights were automatically activated by photocells. These were fairly effective for bats but did nothing to discourage visits by other animals.

Although our original enclosure concept remained beyond reach, in 2009 we implemented an alternative concept for Area 1 with excellent results. We enclosed the sides of the roof with fine mesh, which is practically invisible (helped by its green paint) but works to prevent entry of the animals mentioned above. The mesh is supported on unobtrusive steel frames. The mesh needs periodic maintenance, including a new coat of anticorrosive paint each year and any necessary repairs.

|

|

| The torogoz is a beautiful bird, but it tunnels its nests into the vertical cuts of volcanic ash which loosens them and can also affect the ancient structures. Its scientific name is Eumomota superciliosa. Another name used in El Salvador for the torogoz is talapo. | |

|

|

| LEFT: A fox has left its tracks on the cornfield next to Structure 6. RIGHT: Antonio Menjivar points to damage caused by foxes on Structure 6, where they opened a hole in an area that was apparently previously excavated, since the displaced earth contained shreds of plastic and fabric. |

|

|

|

|

Bats hang from the roof beams and drop guano and seeds on the ancient structures. These photos show Structure 7. Left: The red circles frame fallen seeds on the structure, while the solid dots mark seeds on the surrounding surface. On occasion, the impact of a seed is forceful enough to damage a structure. Right: A closeup of the structure showing seeds and guano. |

|

Most of the seeds are of the tree called "almendro de río" (Andira inermis). Bats eat the pulp and discard the large seeds.

As a provisional measure to keep bats from roosting, in 2006 we installed automatic lights over the archaeological structures. This view shows some of the 12 lamps installed in Area 1. While effective against bats, the lights did not discourage other animals.

|

|

|

In 2009, FUNDAR enclosed Area 1 using some 350 square meters of fine mesh (including 2 doors) in order to prevent the entrance of animals. The mesh is nearly invisible. Appearing in the photo (from left to right) are Francisco Campos (master mechanic), Rodrigo Brito (President of FUNDAR), and Antonio Menjívar (head de Joya de Cerén). The enclosure has been very effective. FUNDAR had proposed to do the same with the other areas at Joya de Cerén, which currently remain unprotected. |

|

In collaboration with the Government between 2005 and 2009, FUNDAR has carried out many changes at Joya de Cerén. In addition, during 2008, CONCULTURA obtained government funding in order to contract special projects at Joya de Cerén and San Andrés, and they allowed us to participate in planning the use of those funds. At Joya de Cerén the special projects included: 1) a new roof to protect Structure 4, 2) the conversion of an asphalt street into a pedestrian trail, 3) construction of a decorative wall to improve the appearance of the park, 4) remodeling of the site museum, and 5) construction of a new ticket booth.

2008: The conversion of an asphalt street into a pedestrian trail was one of the special projects at Joya de Cerén. From left to right: Architect Irma Flores (CONCULTURA, supervisor of the special projects at Joya de Cerén and San Andrés), Rodrigo Brito (FUNDAR), Architect Víctor Barrientos (CONCULTURA, project supervisor, Rafael Amaya (FUNDAR), Antonio Menjívar (Head of Joya de Cerén), and Architect Salvador Torres (representative of the one of the contractors, Pórtico Ingenieros S.A. de C.V.).

These special projects and work by FUNDAR are illustrated below with "before and after" photographs. We begin with the park entrance, followed by the parking areas, the museum, the archaeological trail, and finally the roofs which protect the prehispanic structures.

|

BEFORE The park entrance was nearly indistinguishable from its surroundings. Its worn gates were the same used sin the 1970s when the area was used for silos. To either side of the gate extending rusting cyclone fence set on cement posts, with irregular repairs of barbed wire. A deteriorated sign marked the entrance to El Salvador's only World Heritage site. |

|

AFTER The park is now much more welcoming to visitors. It has a decorative wall of volcanic tuff blocks and a new gate. New signs indicate 100 meters to the park, and the entrance itself. |

|

|

|

|

BEFORE The ticket booth was located on the wrong side of the entrance. It was small and uncomfortable for the fee collectors. The signs were crudely painted and in poor condition. |

|

AFTER The new ticket booth is located on the correct side for interacting with drivers. It is much larger. The sign is bilingual (Spanish and English) and provides more information. |

|

BEFORE One of the first sights for visitors to the park was this: the ugly cement bases which once supported grain silos, all surrounded by weeds. Vehicles were parked in another area, where ground penetrating radar had detected an important buried anomaly (possibly a prehispanic structure). |

|

AFTER FUNDAR filled in the spaces between the concrete bases with compacted earth and covered the area with paving blocks in order to transform this eyesore into a parking area for cars (buses have a separate parking area). We converted the zone with an anomaly (mentioned above) into a picnic area (below).

|

|

BEFORE Another eyesore which greeted park visitors was this old pump house. The arid appearance of this view was typical of the entire park, in which there was very little effort at gardening. |

|

AFTER We covered the pump house with "vara de castilla" cane (used in traditional houses), and we placed two interpretative signs in front (bilingual). We raised a flag and reset here a commemorative plaque naming Joya de Cerén as a World Heritage site. This has now become an orientation spot for park visitors. |

|

BEFORE The Joya de Cerén Site Museum occupied a fairly new building (2003), but visitors compared its design with a shoe box. In spite of the height of the building as viewed from outside, its interior was limited by a low ceiling and relatively little floor space. This space was split up by the use of permanent partitions. The partitions made guarding the museum more difficult. In fact, the two thefts of artifacts from the museum (1997 and 2004) were from display cases hidden from the guard's view behind these partitions. The museum had 2 access doors, one at each end of the building, something that also weakened security. One door served as the entrance and the other as the exit. |

|

AFTER The museum has been remodeled. The interior space was increased by 25%. The internal partitions were removed and the entrance and exit are now together, all contributing to security. The two projections on this side of the building are new. One is for use by the park guides, and the other is for a future museum store. The museum is presently closed while new exhibits are prepared. |

|

BEFORE The snack bar was in bad shape. |

|

AFTER The ceiling was repaired and equipped with lamps. The lattice bricks on the sides were removed in order to open up an unnecessarily confining space. |

|

BEFORE Park visitors entered the archaeological zone without supervision. |

|

AFTER The park now has zonification of uses. Visitors may only enter the archaeological zone with a park guide (identified by their yellow uniforms). The guides provide interpretation of the site and also supervise their groups to avoid any damage to the structures or installations. A guard is stationed in the archaeological zone for support purposes. |

The archaeological trail leads visitors (with their guide) in a circuit offering views of 10 prehispanic structures.

Before the involvement of FUNDAR, this circuit consisted basically of a straight line, entering and exiting along the same route. It did not include Area 2 with the temascal and other very interesting structures. Most of the walk was along a paved street built years ago for trucks. Visitors had to view the ancient structures through cage-like barriers supported on rusted posts made of salvaged iron.

Now the circuit is three times as long and includes Area 2. The circuit loops through the site, without passing over any segment twice. Handrails have replaced the former cage-like barriers. The paved street has been transformed into a pedestrian path. The whole trail, like the park in general, is now flanked by gardens, with flowering plants as well as cacao trees and other traditional crops so that visitors may learn first-hand about our agricultural heritage.

|

BEFORE The blue line indicates the archaeological trail as it existed up to 2005. |

|

AFTER Between 2005 and 2009, FUNDAR extended the trail by a factor of 3, including the formerly "restricted" Area 2. Access is now through a control gate (red). The new parking area is marked in green. |

|

BEFORE Most of the "trail" consisted in this asphalt street. |

|

AFTER This segment of the trail has been converted into a pedestrian path surrounded by gardens. |

|

BEFORE This was the end of the trail at Joya de Cerén: a cage-like dead end of cyclone fencing pegged to posts made of scraps of iron (Area 1). The part of the roof to the right was of "provisional" construction with buckled sheet metal and rotted pine wood. |

|

AFTER This former dead end is now part of the trail circuit. The "cage" has been replaced with handrails. The precarious improvised roof section has been replaced with a solid structure. |

|

BEFORE Park visitors had to shuffle along a narrow access limited to one side of Area 1 (the largest archaeological area). They had to strain to see the archaeological structures in the gaps between tarps which had been hung to "protect" the structures. The interior of this area was consequently kept in gloomy darkness. |

|

AFTER The same view. Now visitors walk commodiously around 3 of the 4 sides of Area 1, with full views of its 5 structures. Skylights now allow everything to be seen with clarity. A huge new roof extension (visible on the left) now gives real protection against wind and the driving rain that commonly come from this north side. |

|

BEFORE Area 2, with the temascal and other structures, was inexplicably off-limits as a "restricted zone" Only VIP visitors were allowed. This photo was taken when we began to set up posts and ropes to include this area in the archaeological trail. |

|

AFTER The same area, now in use as part of the trail surrounded by gardens. We have painted many of the sheet metal roofs green in order to make them less obtrusive. |

|

BEFORE This is another new segment of the trail made in order to include Area 2. Here the segment has been begun, removing unsightly cement posts. |

|

AFTER The same view with the trail segment finished. |

We have planted more than 80 cacao trees next to the trail. Left: Karen Bruhns in the "cacahuatal" (cacao plantation) at Joya de Cerén. Right: ripe cacao pods. The archaeological excavations at this site have discovered cacao seeds and the cavity left in volcanic ash of an actual cacao tree which was growing next to Structure 4. The park guides use these plants as living interpretative resources to help explain daily life at Joya de Cerén.

Feliciano Torres is one of the people responsible for Joya de Cerén's extensive gardens. He is posing next to "malanga" (Xanthosoma spp.) plants along the trail.

Before the introduction of commercial hybrids, several traditional varieties of maize were sown in El Salvador. These have been poorly documented. One variety that remains fairly common is called "maíz negrito" (black corn) because its use in a traditional beverage called "chuco". Its name is due to the dark color (actually dark purple) of its grains. Another traditional variety of corn is known as "maíz nacional" (national corn). Feliciano Torres strives to keep both varieties planted along the trail.

Other traditional cultigens found archaeological at Joya de Cerén include varieties of squash and beans. Visitors can see living examples of both, depending on the season of the year. The type of bean on the left is called "frijol mica" (monkey bean) and its morphology is similar to some of the beans found in excavation. Squash (on the left) is known in El Salvador by the Nahua-derived word "ayote", while in Mexico and most other Spanish speaking countries the word "calabaza" is used.

Roofs for Protection of the Prehispanic Structures

The negligent condition of Joya de Cerén in 2005 was most notable in the roofs built to protect the prehispanic structures from the rain. There were 3 industrial "permanent" roofs, and one of improvised construction that was recognized in 1997 as being so precarious that its potential failure represented an immediate threat to the structure it was meant to protect (Structure 4).

|

BEFORE Structure 4 was "protected" by a precarious improvised roof, identified since 1997 as in danger of collapse. This roof appears here, along with the beginnings of a new roof. |

|

AFTER The new roof as finished (2009) after dismantlement and removal of the old roof. Architect Irma Flores, construction supervisor, appears here. The new roof is joined to that covering Structure 3. The vertical excavation cuts surrounding both prehispanic structures may now be eliminated or modified to stable slopes. |

Archaeological excavations had to be carried out before building the columns for the new roof. Archaeologist Claudia Ramírez (Departament of Archaeology)) was in charge of this investigation, with the participation of Archeologist Claudia Alfaro of the Department of Investigations of the National Museum (MUNA).

Although they are of very solid construction, the 3 industrial roofs had several shortcomings:

- Sheet metal roofing with numerous holes and warping, allowing the passage of rain water.

- Roof extensions supported on rotted pine wood or by rusted iron scraps.

- General lack of tensors which are essential for the stability of this type of roof.

- In Area 1, tarps were used to cover its north side for protection against wind and driving rain. In addition to being ineffectual, the tarps blocked the view of the archaeological structures.

- The interior of all 3 roofs was dark and made viewing and photography of the structures very difficult.

We began with an evaluation of the industrial roofs with a structural engineer, Juan Kerrinckx.

The first recommendation was to add tensors to the 3 roofs, these being necessary for their stability.

Improvements to the Roof of Area 2

|

BEFORE The roof over Area 2 had a large extension in its western side, supported on rotted pine wood and covered by deformed sheet metal full of holes. |

|

AFTER We built a new roof extension supported on a steel framework, covering 350 square meters (approximately 3,800 square feet).

|

|

BEFORE Area 2 was so dark that visitors could hardly make out the ancient structures. One "measure" taken was to remove sheet metal from the rear of the structure, adding glare but little visibility. It also brought the temascal into direct contact with sunlight, which was probably not advisable. |

|

AFTER FUNDAR installed skylights which now ensure suitable illumination. |

Improvements to the Roof of Area 1

Area 1 has the largest number of prehispanic structures (5). Here we built new roof extensions on each of its 4 sides, with a total area of over 600 square meters (approximately 6,500 square feet).

|

BEFORE The north side of Area 1 was the only part accessible to visitors. Driving rains normally come from the north, and this side was "protected" using tarps. In addition to being ineffectual, the tarps blocked viewing of the ancient structures. |

|

AFTER We built a very large roof extension supported on a steel framework and equipped with skylights (see additional photos under The Archaeological Trail). These photos show the framework, the roof as finished with skylights, and the roof with the asphalt street transformed into a pedestrian trail. |

|

BEFORE The western end of the roof covering Area 1. |

|

AFTER We replaced it with solid construction. |

|

BEFORE The eastern end of the roof covering Area 1. |

|

AFTER Our solid new roof extension covers much more space. The additional area will allow the excavation cut next to Structure 12 to be reduced to a stable angle (its potential collapse has been recognized as a threat to the structure). |

|

BEFORE The southern end of the roof covering Area 1. |

|

AFTER In a first stage, we repaired the existing roof. We later built an 8 meter extension in this side, removing the old roof. This is sufficiently wide to prevent entry of rain. The extension now allows visitors to see luxuriant vegetation as a backdrop to the structures. The archaeological trail now courses along 3 sides of Area 1. |

|

BEFORE Area 1 was very gloomy indeed. This photo shows Structure 10 with its base wet (because of the former practice of spraying down the structures), adorned with safety tape and a crude sign. An out of place banner is visible in the background. |

|

AFTER Structure 10 is now illuminated by a skylight, with tape, sign, and banner removed. The roof extension is visible in the background. FUNDAR installed skylights in Areas 1, 2, and 3. |