News about FUNDAR's Investigations and other activities

June-July, 2012

The search for a 1,500 year-old tree

An ancient tree could hold the key to solving the problematic dating of Ilopango’s huge eruption, and confirm the theory advanced by Dr. Robert Dull and others that its impact was not just regional, but worldwide.

In June and July, 2012, FUNDAR collaborated in a study which aims to narrow the dating of Ilopango’s TBJ eruption, which in this region was the worst natural disaster in all human history. Due to certain factors, it is essential to find a tree which was already old at the time of the eruption, somehow preserved under the mantle of the “tierra blanca” (“white earth”, the local name for Ilopango’s ash). This investigation is led by Robert Dull.

What follows is an overview of the problem addressed by this study, and a narration of the discovery of an ancient tree which could help in solving it (text and photos by Paul Amaroli).

Lake Ilopango is beautiful, but 1,500 years ago the megaeruption of its caldera destroyed the southeastern area of the Maya World, and may have had worldwide repercussions.

Ilopango’s eruption released some 20 cubic miles (80 cubic kilometers) of fine white tephra, known as “Tierra Blanca Joven” (young white earth), or TBJ for short. Near the lake you can find TBJ deposits over 180 feet (60 meters) deep. This volcanic ash is easily eroded as can be seen in this huge gully. Even at 50 miles distance, exposures with a foot and a half of TBJ have been found.

The eruption began with pyroclastic flows reaching up to 30 miles from the caldera, which generally incinerated everything in their path – including tens of thousands of humans. This was followed by the TBJ ash fall which covered a far greater area and led to the eventual death of many more people and the displacement of refugees who managed to survive. Today the TBJ deposits are exploited for use in construction and to manufacture artisanal bricks and roof tiles.

A traditional brickyard with TBJ ready to be mixed with sand, clay, and water. The mixture is packed into molds, then dried and fired in the kiln visible in the background.

These kilns are fired for about 12 hours. During this time it must be fed firewood constantly.

TBJ exposures are also exploited by El Salvador’s national bird, the torogoz, which excavates its tunnel-like nests in the friable ash. This torogoz is delivering a caterpillar to its chicks.

There are problems in dating the Ilopango TBJ eruption. Three decades

ago, its date was estimated at AD 260. In 2001, Robert Dull, together

with other scholars, published a new date, of approximately AD 410-540

(2 sigma), using carefully selected samples and AMS radiocarbon analysis.

Dull has since continued to investigate this dating. Several branches

or small tree trunks have been found which were toppled and carbonized

in pyroclastic flows, like those illustrated here. Dull has obtained some

13 dates from samples taken from the surface of a trunk from a tree killed

by the eruption, and independently FUNDAR sponsored radiocarbon dating

of a surface sample taken by Paul Amaroli from the trunk shown here (from

the entrance to the Los Chorros “turicentro”). Unfortunately, as Dull

has described, although the results coincide in that the eruption could

have been around AD 530-540, the irregularities of the calibration curve

for this period introduce excessive error (or rather an ample range of

probabilities). Dull and others have suggested the captivating possibility

that Ilopango’s eruption may have caused the so-called “Great Dust Veil

Event” recorded in documents from Europe and Asia in AD 536. Exceptionally

cool weather led to crop failure and famine. Tree rings also indicate

worldwide cooling at this time. Sulfate spikes dating to about AD 530-540

have been found in the ice caps at both poles suggesting that this global

cooling was caused by a large volcanic eruption situated roughly at some

intermediate point very likely in the tropics, as is the case for Ilopango.

But for this linkage to Ilopango to be credible, it is necessary to tighten

the eruption’s dating.

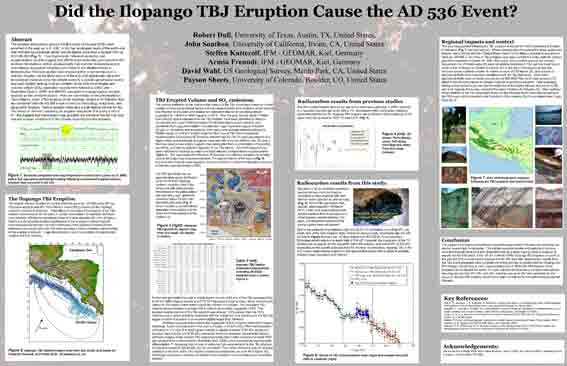

The theory that Ilopango’s eruption caused the worldwide event of AD 536 was summarized by Robert Dull and colleagues in this poster presented at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union held in 2010 at San Francisco (click on the image to see a larger version).

Dr. Robert Dull (left) and Geologist Walter Hernández (right) inspect a TBJ exposure near the town of Verapaz (San Vicente Department).

How then to refine the dating of Ilopango’s TBJ eruption? In June, 2012, Robert Dull contacted Paul Amaroli to collaborate in the search for a large tree trunk buried under TBJ. The heart of a large trunk – that is, of a venerable tree – could be old enough to predate the period of great irregularity in the radiocarbon calibration curve, giving a firm point of reference to clarify the later mixed probabilities previously mentioned. Several years ago Amaroli had heard rumors that tree trunks had been found in a TBJ extraction pit, but it wasn’t possible to enter the area. Now, with the renewed interest, the area was revisted with archaeology student Edgar Cabrera. No TBJ has been mined here for quite a while, but thanks to the help of a local resident something was found which left a deep impression: an ancient tree, still standing under the TBJ. Amazingly the people mining TBJ had seemingly respected the tree, leaving it exposed in a vertical cut. And not only that, but the tree was preserved as wood, not charcoal (its surface is slightly blackened), apparently because the pyroclastic flow reaching this spot was not hot enough to carbonize it, and because the tree was hermetically sealed, and thus protected, by the TBJ.

Close-up of the tree’s surface. It is extremely rare to find ancient wood preserved in this region with its warm and humid environment.

The goal then was to take samples from the tree. Under a permit granted by the Secretaría de Cultura and with the help of the crew from Cihuatán, the TBJ was removed from around the tree. This photo was taken during this process, and two branches (or small trunks) can be seen which were tumbled against the trunk by the pyroclastic flow. The same violent flow snapped off the upper part of our tree. Special thanks to Gustavo Milán (National Director of Cultural Heritage, Secretaría de Cultura) for authorizing this work.

The pyroclastic flow’s violence is also shown by the numerous fragments of twigs and shattered wood found in the TBJ matrix surrounding the tree.

The tree was exposed down to the ground level existing at the time of the eruption (the paleosol) which was dark brown in color. It was remarkable to find the roots intact and still tenaciously gripping the earth. You can see in the photo how the TBJ accumulated in curving layers over the then-exposed beginnings of the roots. The tree’s sturdy root system undoubtedly helped to keep it standing during the eruption. Please note that this was not an archaeological excavation, but rather a quick geological exposure which for a variety of reasons had to be completed within a single day.

The crew poses with a 1,500 year-old tree. With Pastor Gálvez, Miguel Angel Pineda Pineda, Miguel Angel Pineda Castillo, Antonio Castillo, Rutilio González, and Paul Amaroli (photo by Edgar Cabrera).

As mentioned, the goal was to take important samples, consisting of sections (disks) of the trunk. This was undeniably sad, although there can be no doubt that this tree was destined for prompt destruction. When it was partially exposed years ago, its “seal” of TBJ was broken and destructive processes were set in motion. Part of the tree was now found to be invaded by termites, and an ant nest was in another part. There were also signs of rotting. This photo shows a chainsaw being used to fell a 1,500 year-old tree. The wood was extremely hard and dense. A film crew was present - they are making a documentary about the Ilopango eruption with Robert Dull.

A section was cut from the trunk which was

later divided into several slices for sampling. The trunk has been deposited

in the MUNA (the National Museum) and will hopefully someday be used in

an exhibit about the Ilopango eruption.

Robert Dull and the film crew.

One of the sample sections. In some sections the heart was loose but we recorded its correct position. The first cut measured 57 to 69 centimeters in diameter. The type of tree will be ID’ed; people familiar with local trees think it may be chichipate (Acosmium Panamense) or copinol (Hymenaea courbaril).

Ilopango’s caldera has had four huge eruptions (and several minor ones) which are referred to from latest to earliest as TB1 to TB4 (it also had much more ancient episodes, but those are another story). The TB1 eruption deposited the very white tephra known as “Tierra Blanca Joven” (TBJ) around the sixth century AD, a time when this region was densely populated. It is thought that the oldest eruption (TB4) took place some 30,000 or 40,000 years ago. For the purpose of illustration, the sequence is squematically overlaid on this construction cut. Ilopango's more ancient eruptions have been studied by Salvadoran geologist Walter Hernández and specialists from other countries.

There is much evidence that this region was densely populated at the time of the Ilopango TBJ eruption. When construction cuts penetrate beneath the TBJ, they provide views of the landscape buried 1,500 years ago. And everything indicates that this was an intensively cultivated landscape, divided into farmed plots and others left fallow. Dozens of ridged fields covered by TBJ have been noted in terrain ranging from level areas like the Zapotitán Valley to relatively steep locations like the hills on the road to Huizúcar (pictured). Evidence indicates that they were used for corn and manioc, and it is likely that some were used for other crops. On the other hand, trees and shrubs are almost never found in exposures of the TBJ and the underlying ground surface. It may be conjectured that the territory deeply covered by TBJ held at several important Maya centers, each of which would have dominated a network of minor settlements. Where are they? Sherds and obsidian have been found in the ancient soil covered by TBJ revealed at several construction cuts, but in many cases these belong to archaeological sites which were already ancient at the time of the eruption.

In rare cases the ridged fields are associated with bell-shaped pits often excavated to depths of about 4 to 6 feet. These are domestic features common in Preclassic Mesoamerica and are found distributed closely around houses. It is thought that their purpose was to store grain, although their final use was often as trash dumps or even tombs. None of the features found to date were in use when the TBJ fell. The photo shows a ridged field with a bell-shaped pit marked with an arrow. The field passes over the mouth of this feature, demonstrating that it was not in use at the time. This field is located along the entrance to the Saburo Hirao Park within metropolitan San Salvador.

Ilopango has also had many minor eruptive episodes. The latest eruption – which fortunately was very limited – occurred between December 1879 and March 1880. The eruption proceeded with earthquakes and swift changes in the lake’s level. A vapor column surged out of the lake (shown in this etching) and new lava broke the surface, forming what are known as the Cerros Quemados. Ilopango has been studied by numerous specialists.

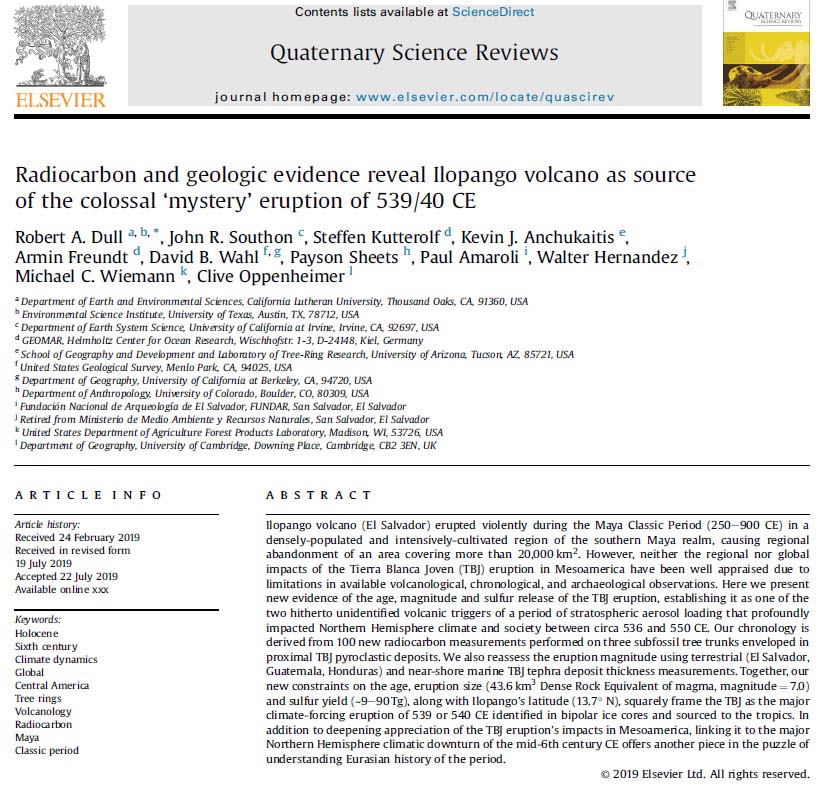

2019: Publication of Results

In July, 2019, an article was published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews presenting the results of the tree study, together with other studies about Ilopango's megaeruption. The article is titled "Radiocarbon and geologic evidence reveal Ilopango volcano as source of the colossal 'mystery' eruption of 539/40 CE", by Robert Dull, John Southon, Steffen Kutterolf, Kevin Anchukaitis, Armin Freundt, David Wahl, Payson Sheets, Paul Amaroli, Walter Hernández, Michal Wiemann, and Clive Oppenheimer.

The new geological studies indicate that the volume of Ilopango's eruption was much greater than supposed, with a minimum of 106.5 cubic kilometers of tephra. This means that it now qualifies for a VEI (Volcanic Explosivity Index) of 7, now ranking Ilopango among the planet's 10 greatest eruptions of the past 7,000 years.

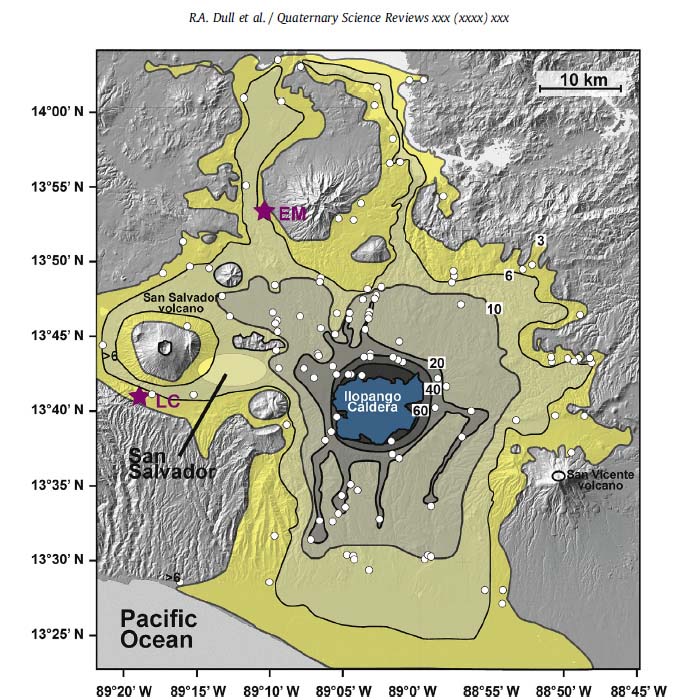

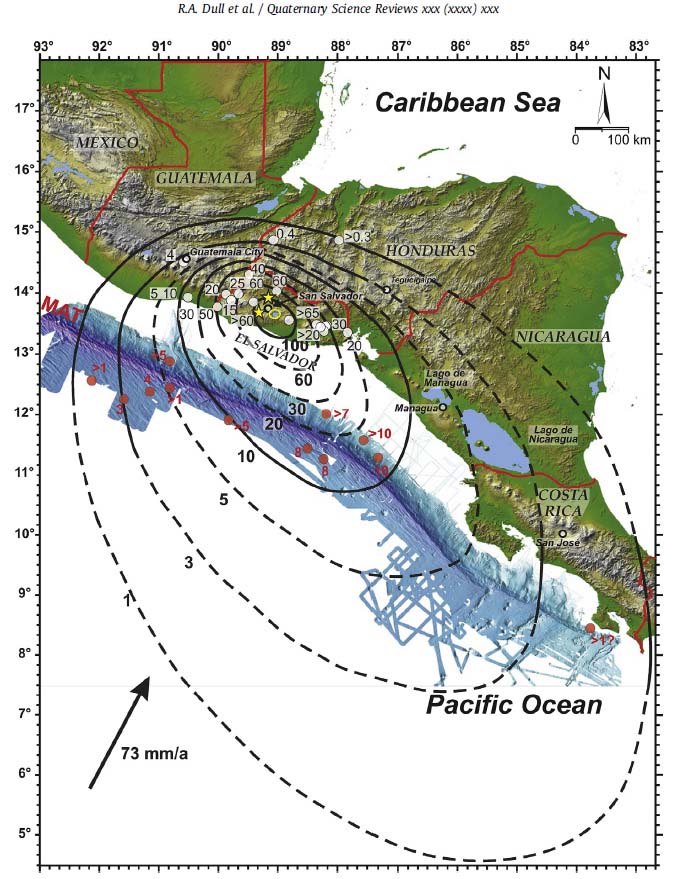

The geological studies also show that the eruption's reach was much greater than previously known. In its first stage, tremendous pyroclasitic flows erupted from the caldera with velocities in excess of 200 kilometers per hour, consisting of extremely hot gases and tefra, capable of carbonizing trees (and people) on their path. It has now been shown that these hellish flows covered over 2,000 square kilometers. These were followed by the deposition of tephra (ash and other airborne materiales) which, while less violent, covered much more territory. The two following maps are taken from the article and illustrate the pyroclastic flows and the reach of tephra. It is estimated that the eruption killed hundreds of thousands of people - the hemisphere's greatest loss of human life up to the European invasions with the pandemias they brought.

Extent of pyroclastic flows. Numbers show thicknesses in meters.

Extent of tephra. Numbers indicate thicknesses in centimeters.

In regard to when Ilopango erupted, radiocarbon dating was carried out for some 100 samples from the tree under discussion, and from another tree, of secondaria importance, found a few meters away. Together with dates taken previously from a sample from Los Chorros, it is calculated that the eruption took place between AD 503 and 545 with a probability of 95.4%. Statistical analysis of the results indicate that the eruption was probably in AD 539/540.

Studies of "spikes" of sulphates in the polar ice caps indicate that two megaeruptions took place between AD 535 and 540. The first was around AD 536, located well within the northern hemisphere at a yet-undetermined volcano, as its sulphates were only represented in the north polar ice cap. The second eruption, around AD 540, deposited sulphates in both poles, suggesting that its source was in the tropics, and Ilopango is now presented as its origen. Both eruptions acted to cool the planet during several years, leading to the failure of crops in Europe and Asia.