Cihuatán Archaeological Park

During the 1950s, for the first time in Salvadoran history, the government purchased important parts of two archaeological sites for their protection: Cihuatán, where 10.5 hectares (26 acres) were acquired in 1953 (including its Ceremonial Center), and the area of mains structures at Tazumal. In 1994, thanks to the efforts of Antonio Cabrales (then Minister of Agriculture), the Government purchased another 61.3 hectares (151 acres) at Cihuatán, with which protection was extended to the Acropolis and an ample sector of the ancient residential area. Now counting a total of 71.8 hectares (177 acres), Cihuatán is El Salvador's largest archaeological park.

CONCULTURA (replaced in July, 2009 by the Secretaría de Cultura) was the government agency responsible for the national archaeological parks. In December, 1999, FUNDAR signed an agreement with CONCULTURA to co-manage Cihuatán and to undertake the Cihuatán Project.

FUNDAR began work at Cihuatán in the year 2000. At that time Cihuatán was virtually abandoned. The site's workers were able to keep only a small area of the site clear, which for the most part was covered with brush that was burned every year by vandals (taking advantage of the lack of guards) in order to hunt small game (armadillos, black iguanas, and opossums) driven out by the fire. The fires were also intended to kill the occasional small tree which had struggled to grow in these adverse conditions, to be later chopped up for use as firewood. The site house was repeatedly looted by groups of youths who would congregate when the site workers departed. The site house and an adjacent structure had been turned into improvised storerooms for cultural materials (mostly sherds) from past excavations at sites all over the country, filled with stacks of about 5,000 sacks - largely split and spilling their contents - in conditions which were far from appropriate. There was no electricity or water. Visits to this desolate place were at one's own risk.

After 8 years of cooperative work, FUNDAR and CONCULTURA inaugurated Cihuatán as an archaeological park on November 17, 2007. FUNDAR and other donors have contributed over $300,000 to Cihuatán (see the section Improvements by FUNDAR).

In 2009, FUNDAR decided to end its participation in park management in

order to fully dedicate itself to the investigation and dissemination

of El Salvador's archaeological heritage. In July, 2010, FUNDAR and the

Secretaría de Cultura signed a new agreement for the co-administration

of Cihuatán, in which FUNDAR continues with its research project (click

here to read more about this agreement).

The Cihuatán Project is one of FUNDAR's main activities. Cihuatán has long been recognized as the largest archaeological site in El Salvador (although we now know that it is exceeded in size by the neighboring site of Las Marías). The ancient city of Cihuatán arose following the enigmatic "Maya Collapse" and became a regional capital between AD 900 and 1200 (the Early Postclassic period).

The main pyramid at Cihuatán (Structure P-7) with Guazapa Volcano in the background.

The Government of El Salvador owns an important part of Cihuatán, where

FUNDAR has cooperated to create an archaeological park. The objectives

of our project have included:

- Starting off with a completely neglected site, implement the management of Cihuatán.

- Contribute to public education regarding Cihuatán and archaeology in general.

- Advance the investigation of Cihuatán and other sites in its region.

- Contribute to the conservation, consolidation, and restoration of its prehispanic architecture.

- Identify other sites in the area for their study and protection.

- Make Cihuatán a destination for national and international tourism, which will contribute to the auto-sustainability of the park.

- Create new economic opportunities for the surrounding population.

Click here for the latest project news.

Participants in the Cihuatán Project

Many people and institutions have contributed to the Cihuatán Project.

The institutions and groups which have participated include:

- The Government of El Salvador, via its cultural wing, which has extended permits, maintained supervision, and has directly participated in the project's activities.

- USAID, which donated an endowment to FUNDAR. The interests from this fund supports the Cihuatán Project.

- San Francisco State University, California, represented by Professor Emeritus Dr. Karen Bruhns.

- The Sol Meza Family (grandchildren of Antonio Sol, who, in 1929, was the first to conduct official archaeological excavations in El Salvador), who donated funds for remodeling the dilapidated site house, converting it into a site museum, laboratory, and maintenance area, with restrooms for visitors.

- The Kislak Family Fund, USA, through the good offices of Jay Kislak, whose donation contributed to the creation of the park.

- The Ford Motor Company, which awarded FUNDAR its Conservation and Environmental Grant in order to build a water system for the site house which captures and stores rainwater from the roof.

- The Municipality of Aguilares, which has helped in maintenance of the park's access road and in supplying water for the site house.

- The Office of Public Affairs of the US Embassy in El Salvador, which has awarded two grants to the Cihuatán Project: 1) a grant for building public access stairs for the main pyramid and ball court and for conservation of the ball court, and 2) a grant for the investigation and conservation of the Acropolis.

- The Hospital de Diagnóstico of El Salvador, under its cultural program, has made important donations to the project.

Supervision visit to monitor FUNDAR's endowment fund. From left to right: Pastor Gálvez, Laura Morales, Zachary Revene, José Ramón Zapata.

From left to right: Ricardo y Enrique Sol Meza, Rodrigo Brito, Federico Hernández.

On behalf of FUNDAR, Paul Amaroli receives the Ford Motor Company's Conservation and Environmental Grant for Cihuatán.

Donna Roginski (Public Affairs Officer, US Embassy El Salvador) holds a commemorative plaque in front of the visitor access stairway at Cihuatán's main pyramid. This and two other stairways at the site were financed by a grant from her office.

From left to right: Rodrigo Brito, Hilda Guerra and Marjorie Stern (both from the Office of Public Affairs of the US Embassy) atop the main pyramid at Cihuatán. A grant from their office also provided funds for conservation work at the North Ball Court (visible in the background).

Individuals who have participated in the Cihuatán Project include:

- The head of the Cihuatán Archaeological Park, Pastor Gálvez, who with his staff of workers is responsible for maintenance of the park. Gálvez has three decades of experience archaeological excavation with projects conducted by several archaeologists.

- The co-directors of the Cihuatán Project, Karen Olsen Bruhns,

who has been committed to the investigation and protection of Cihuatán

since 1975, and Paul Amaroli. You can find ample information

about the Cihuatán Project on our sister website, www.cihuatan.org.

Pastor Gálvez (Head of Cihuatán) y Dr. Karen Bruhns on the Acropolis. Guazapa Volcano rises in the background.

Other people who have participated in the project include:

- Archaeologist Fabio Amador (El Salvador), as a member of FUNDAR co-directed with Paul Amaroli the reconnaissance of the limits of Cihuatán and the investigation of its main pyramid.

- Archaeologist Matilde Gil (Spain), participated in mapping and reconnaissance at Las Marías and other sites.

- Archaeologist Claudia Ramírez (El Salvador), participated in excavations at Carranza, in addition to her role as a project supervisor assigned by the Government.

- Archaeologist Heriberto Erquicia (El Salvador), participated in an excavation at Las Marías in addition to his role as a project supervisor assigned by the Government.

- Archaeologist Marlon Escamilla (El Salvador), participated in an excavation at Las Marías in addition to his role as a project supervisor assigned by the Government.

- Archaeologist Vladimir Avila (El Salvador), participated in excavations at Carranza and Cihuatán, and in reconnaissance at Las Marías and other sites.

- Archaeologist Zachary Revene (USA), participated in excavations at Cihuatán and other sites. He also planted 500 trees of native species along Cihuatán's access road.

And the following archaeology and anthropology students:

- Federico Paredes, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (now graduated)

- Liuba Morán, Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador (now graduated)

- Miriam Méndez, Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador (now graduated)

- José Camarena, San Francisco State University, California

- Astrid Francia, Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador

- Rebeca Gámez, Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador

- Edgar Cabrera, Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador

- Alejandro Teba, Universidad de Sevilla, Spain

- Luis Sibrián, Universidad Tecnológica de El Salvador

Pastor Gálvez (left) and Fabio Amador during the investigation of the main pyramid at Cihuatán (Structure P-7).

Vladimir Avila, Feliciano Torres, Liuba Morán, and Miriam Méndez on the site limit survey of Las Marías.

Marlon Escamilla and Federico Paredes FUNDAR's annual picnic at Cihuatán.

Leslie Lane and Federico Paredes in the investigation of the main pyramid.

Heriberto Erquicia, Vladimir Avila, Mario Portillo, Feliciano Torres and Paul Amaroli at Las Marías.

Claudia Ramírez and the salvage excavation crew at Carranza.

Zachary Revene and Pastor Gálvez during conservation work at Structure P-5 in the North Ball Court.

José Camarena (standing with a gray T-shirt), Zachary Revene (drawing) and personnel of Cihuatán in the temazcal (sweat bath) excavated by Antonio Sol in 1929.

From left to right: Jorge Colorado, Astrid Francia, Edgar Cabrera, Karen Bruhns, and Paul Amaroli in front of the Acropolis at Cihuatán.

Alejandro Teba and Edgar Cabrera take measurements at the Acropolis.

Matilde Gil (left) and Karla De León during the limits survey of Tehuacán (a study requested by the Municipality of Tecoluca).

Description of the Ancient City of Cihuatán

The North Ball Court. Cihuatán has two ball courts.

Cihuatán has long been considered the largest archaeological site in El Salvador, covering about 3 square kilometers (approximately 1.2 square miles). The city is strategically located on a broad, low hill which dominates the ample valley formed by the Acelhuate and Lempa rivers. The horizon east of Cihuatán is punctuated by the rugged peaks of Guazapa Volcano.

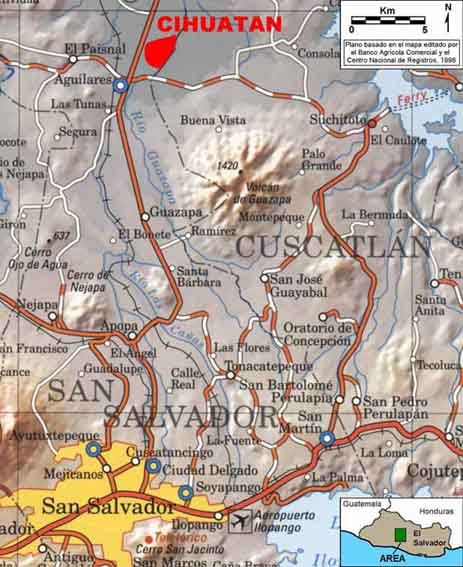

Cihuatán is located in central El Salvador, about 36 kilometers north of San Salvador.

An oral tradition which may still be heard from old-timers in this area describes how the rough peaks of Guazapa Volcano resemble the silhouette of a sleeping woman. The place name "Cihuatán" is from the Náhuat language (originally "Ciwátan", with penultimate accent) which was spoken in this area at the time of the Spanish conquest. It may be translated as "Place Next to the Woman".

Guazapa Volcano as seen from the main pyramid.

Below are the features of the sleeping woman which old-timers distinguish in the volcano's peaks.

Anatomy of

the City

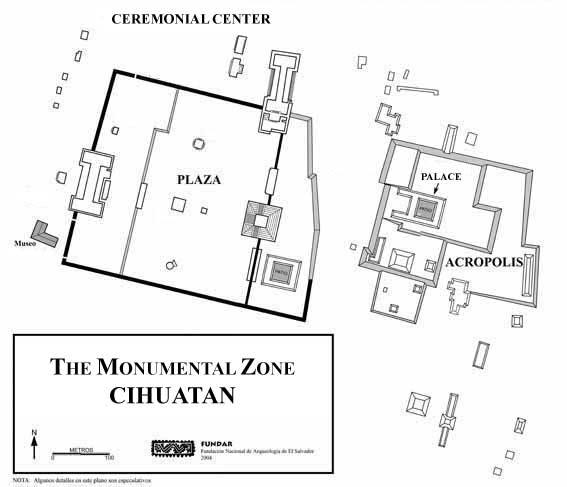

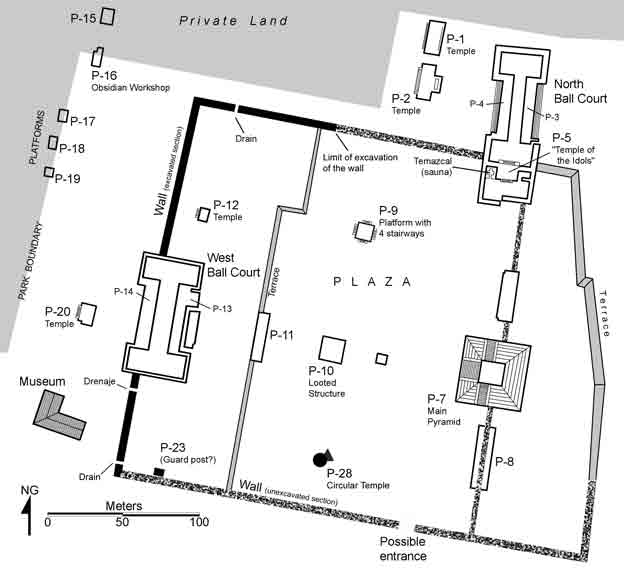

Cihuatán was a truly urban settlement with a large number of houses, temples,

and palaces. Its monumental center covers over 28 hectares (70 acres)

and is divided into two parts, the Acropolis (also called

the Eastern Ceremonial Center) which is as yet little known, and the Ceremonial

Center (also called the Western Ceremonial Center) where most

investigations have been concentrated to date.

Details of the Acropolis are tentative, as is the structure indicated to the southeast of the main pyramid.

The Ceremonial Center (or Western Ceremonial Center) consists of a walled precinct with the main pyramid (Structure P-7), two ball courts, and several other buildings including temples and a structure which may have been an elite residence. Cihuatán's large plaza may have hosted periodic markets and festivals. Monumental construction at Cihuatán typically employs a fill of stone and earth, confined within retaining walls of rough stone which in many cases was faced with blocks and slabs of volcanic tuff (locally called "talpetate") and apparently artificial blocks made like adobe bricks from white volcanic ash (these blocks are known as "talpuja" at Cihuatán). Pumice cobbles, usually with one side ground flat, were also used to face walls and floors, and as chinking between other stones. Many, and perhaps most structures carried a final facing of lime plaster. It is remarkable that the ancient builders obtained lime by burning massive quantities of clam shells (including a type known as "casco de burro" [Anadara sp.]) hauled from their coastal mangrove forest habitat, the closest of which is over 70 kilometers distant. As far as is known, the roofs of structures in this area were of grass thatching.

The Ceremonial Center is open to visitors, and parts of some structures have been reconstructed, including the North Ball Court and the main pyramid. Studies undertaken by FUNDAR have added some previously unknown structures to Cihuatán's map, including a circular temple (Structure P-28) which was investigated in 2005.

The first excavation conducted by FUNDAR at Cihuatán was at the main pyramid (Structure P-7) during 2001 and 2002. The work was directed by Fabio Amador and Paul Amaroli. You can download the report (in Spanish) here (PDF file, 7.6MB).

This circular temple (Structure P-28) was studied in 2005 by FUNDAR. It was probably dedicated to the Wind God (Ehecatl). A report on this work was published by Karen Bruhns and Paul Amaroli in the journal Arqueología Iberoamericana (2:35-45 [2009]). Click here to download the article (PDF file, 1MB).

The Acropolis is not yet open to public access. It is a very large platform upon which are situated several buildings. The first study in this part of Cihuatán was some 40 years ago, when Stanley Boggs investigated a small platform (Structure O-4) just south of the Acropolis. It was unusual in that over 1,000 pounds of ceramic fragments had been dumped over it in antiquity. The ceramics included spiked censers and a wheeled figurine representing a dog. The burial of a young woman was found under this deposit. Next to her were the remains of a dog and several dozen miniature cups.

|

|

| A spiked censer reconstructed from fragments found on Structure O-4. | The wheeled figurine of a dog. Both objects are on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in San Salvador (see Boggs 1973). |

In 2001, FUNDAR identified a possible palace on the Acropolis, and this has been confirmed by the results of excavations conducted since 2005. In many ways this royal palace replicates the general layout and architectural features of similar structures known from central Mexico. It had a flat masonry roof supported upon walls and thick columns built with adobe bricks. The edges of the roof were decorated with ceramic "almenas". It had a large patio and probably several impluvia (small patios for light and ventilation) surrounded by rooms. This type of palace (known as a tecpan) is characteristic of central Mexico where its antecedents reach back many centuries before the Spanish conquest. The study of Cihuatán's palace has only just begun, but it clearly constitutes a major piece of evidence for the important relationship of this site with central Mexico. You can view a tentative digital reconstruction of the palace by clicking here.

The Acropolis at Cihuatán. A plaza separates the Acropolis from the Ceremonial Center (view towards the east). Guazapa Volcano is visible on the right.

The Acropolis (view towards the southeast). The excavations are covered with plastic at day's end.

Excavation in the Palace. The surviving stump of a circular column is in the foreground. Most of the floor here is paved with pumice cobbles, with some rectangular "talpuja" blocks. The slightly sunken area represents an impluvium; the roof was open over this feature for light and ventilation, while the lowered floor acted to confine rain water and lead it to a drain.

Left: Pastor Gálvez with a relatively intact almena next to a major southern wall of the palace. Having fallen from the edge of a roof, most almenas are found shattered into many fragments (like those in the foreground). Right: Detail of the almena.

Tláloc, the rain god, was of great importance to the residents of Cihuatán. This ceramic effigy was found at the western base of the Acropolis during FUNDAR's investigations of the Palace. It is currently in the Conservation Workshop of the National Museum.

This ceramic sculpture was discovered in the salvage excavation carried out by FUNDAR at Carranza, a suburb of Cihuatán which was being destroyed by sugar cane cultivation. It represents a jaguar warrior. The shape of his large pectoral (which still retains vestiges of blue paint) is interesting, as it resembles Classic Maya pectorals crafted in the form of the Ik symbol ("breath", "wind"). Photograph taken at the National Museum.

Cihuatán's monumental core was surrounded by thousands of households. Over 1,200 residential features have been identified to date in surveys covering about one fourth of the residential zone. Karen Bruhns has excavated 17 residential features and found that several were not visible on the surface. Houses were built on low rectangular platforms (faced with field stone and filled with stone and earth), upon which wattle-and-daub ("bahareque") walls were erected and covered by thatched roofs. Terraces were constructed on the slopes of Cihuatán's hill in order to provide level spaces for houses. Karen's 1980 monograph describing her studies of domestic archaeology at Cihuatán is available online by clicking here (PDF file, 12MB).

Jane Kelley, in her study of the San Diegüito sector of Cihuatán, suggests that the residential zone may have been divided into wards ("barrios"), each marked by a neighborhood temple and other special structures. Click here to read her monograph (PDF file, 115MB).

A frequent question about Cihuatán is "how many people lived there?" This is difficult to answer, for the following reasons: 1) surface counts of residential features fall short because we know that there are many more which are "invisible" (slightly buried), 2) not all features were actually houses; some are terraces, others could have had other functions such as storerooms, temazcals, work areas, etc., 3) significant areas of the residential zone have been damaged by recent agricultural activities that have "erased" many features, 4) it is unlikely that all features were in use at the same time, and 5) there is no direct evidence bearing on average family size at Cihuatán. So while a simplistic approach might attempt to estimate Cihuatán's population by multiplying the number of residential features by a supposed average family size, the foregoing shows that this would be pure guesswork.

A residential platform south of Cihuatán's monumental core (Federico Paredes and Pastor Gálvez).

Between 1999 and 2001, FUNDAR conducted reconnaissance in order to determine the limits of the ancient city of Cihuatán, which until then were unknown. This study was done by Paul Amaroli and Fabio Amador. Federio Paredes (then a student) participated in part of the fieldwork. You can download the report of this work here (PDF file in Spanish, 7MB). One result of this study was the definition of a polygon referenced to geodesic points which describes Cihuatáns limits and forms the basis for the protection measures currently in effect for this site (see Our Fight Against Looting and Illicit Traffic of Artifacts).

Foundation

and Abandonment of Cihuatán

According to existing studies, Cihuatán was founded between AD 900. These

were the times following the Maya Collapse, a phenomenon which in many

ways remains enigmatic and constitutes one of the most hotly discussed

topics in Mesoamerican archaeology. The end result of the Collapse was

the near or total abandonment of most settlements in our region between

AD 800 and 900. Cihuatán and its related sites were founded in the aftermath

of this general disaster.

Cihuatán had a brief existence of only some 150 years. Its material culture

(architecture, ceramics, and other artifacts) are strongly related with

the cultures of central Mexico. There are currently three theories about

the inhabitants of Cihuatán. One is that they were immigrants from Mexico

and were the direct ancestors of the historic Pipil who, by the time of

the Spanish conquest, covered the western half of Salvadoran territory.

Another theory is that the city was established by a different Mexican

group, and that its destruction was due to a second wave of migrants (ancestors

of the Pipil?). The third proposal is that its population was mainly of

local ethnic groups which underwent marked changes in their way of life

during the turbulent period marked by the 9th century AD following the

Maya Collapse and its consequences.

The culture represented at Cihuatán is known to archaeologists as the

Guazapa Phase. Several other Guazapa Phase settlements have been discovered

in the same region as well as throughout the western half of El Salvador.

Cihuatán was undoubtedly the capital of an important kingdom.

The city of Cihuatán was destroyed by fire. Excavations in its palace, temples and houses have repeatedly found burnt debris fallen upon floors. Radiocarbon dates indicate that this happened around the year AD 1100. Was it a war that destroyed Cihuatán? This appears very likely to judge from the evidence of a city-wide fire and from the presence of arrow and lance points strewn amongst the debris. It remains for future investigations to resolve this and other major questions about the ancient city.

As far as is currently known, after its destruction Cihuatán was never again reoccupied. By the time of the Spanish conquest (1524) it had been abandoned for about four centuries.

Left: A spiked censer measuring about 1.5 meters in height. Right: Excavations in the palace and temples of Cihuatán have revealed that they were burned suddenly, with censers and other objects shattered on their floors.

Investigations

and Investigators

The earliest known notice which apparently refers to Cihuatán dates from 1859, when a municipal report from Guazapa cites remains of "a large and populous city" in the area (Guazapa is about 11 kilometers [7 miles] south of Cihuatán). About five years later, when the traveler Simeon Habel arrived at the town of Guazapa, he was told his route had passed by "a place called Siwhuatan…remarkable for the many ruins of foundation walls regularly laid out."

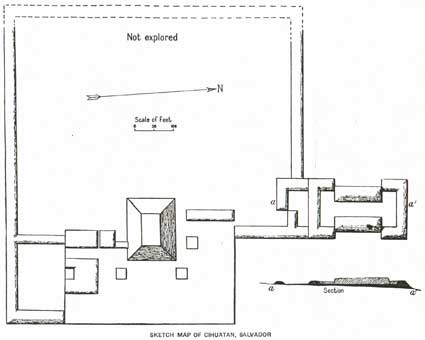

In the period between 1925-26, archaeologist Samuel K. Lothrop visited Cihuatán and prepared the first map of the site.

The first map of Cihuatán was drawn by Samuel K. Lothrop (1926). The main pyramid and North Ball Court are included, as is the wall of the Ceremonial Center. Most of the site was still forested and "not explored" (as noted on the map) at this time.

In 1929 Antonio Sol, assisted by the Italian engineer Augusto Baratta, undertook several months of excavation in the main pyramid and the North Ball Court. This was the first official archaeological excavation in the history of El Salvador.

Left: the north stairway of the main pyramid as excavated by Antonio Sol in 1929. Right: head of one of the 20 ceramic feline sculptures discovered by Sol in the excavation of a structure he called "The Temple of the Idols" (Structure P-5).

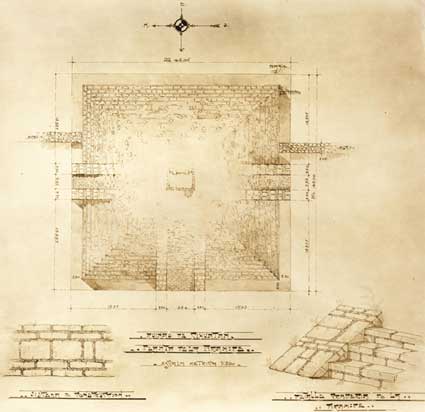

Plan of the main pyramid (Structure P-7) drafted by Augusto Baratta in 1929 (courtesy of Alicia Sol de Morales).

Archaeologist Stanley Boggs conducted important studies in Cihuatán during 1954, 1965, and 1967. The years from 1974 to 1979 saw the contribution of several archaeologists, including Karen Bruhns, Gloria Hernández, William Fowler, Jane Kelley, and Earl Lubensky.

Cihuatán was in one of the most conflictive areas of the civil war of 1980-1992, when Guazapa Volcano became a major guerrilla base. Despite the difficult circumstances, in 1986-87 José Retana, José Salguero, and Gregorio Bello carried out a restoration of the North Ball Court.

In 1996, CONCULTURA contracted the APSIS surveying firm to create a new map of the monumental zone.

The current Cihuatán Project began in 1999 with the

participation of FUNDAR and San Francisco State University, California,

with the support of an endowment received from USAID and the general coordination

of CONCULTURA. Fabio Amador and Paul Amaroli conducted the limits survey

of Cihuatán (1999-2001) and in the investigation of the main pyramid (2001-2002)

which was coordinated by Karen Bruhns. Between 2000 and 2009, in addition

to those already mentioned, the project has benefited from the participation

of Vladimir Avila and Zachary Revene, as well as the following students

of archaeology and anthropology: Miriam Méndez, Federico Paredes, Liuba

Morán, José Camarena, Astrid Francia, Edgar Chacón, Rebeca Gámez and Luis

Sibrián. The work performed has included mapping, excavations in the circular

temple (P-28) and the royal palace, as well as conservation work in the

North Ball Court, Structure P-12, and the palace.

Procedures Regarding Permits and Supervision

The reader may be interested to know something of the permit process for archaeological investigation in El Salvador. In brief, a proposal is submitted to the Secretaría de Cultura which includes a description of the proposed project. Though previously only vaguely defined, the procedures and requirements were published in 2007 as the "Normativa de regulación de investigaciones arqueológicas de El Salvador", and of course FUNDAR complies with these. A Government supervisor is assigned to each project.

A supervisory visit to Cihuatán. From left to right: Fabricio Valdivieso, Paul Amaroli, Juana Toledo, Rodrigo Brito and Federico Hernández.

Government archaeologists who have been assigned to supervise FUNDAR projects have inlcuded:

- Marlon Escamilla

- Heriberto Erquicia

- Claudia Ramírez

- Fabricio Valdivieso

- Shione Shibata

The Antonio Sol Museum of the Ancient City of Cihuatán

The Antonio Sol Museum was so named after Antonio Sol, the investigator who undertook the very first archaeological excavations in El Salvador. These were conducted at Cihuatán during 1929. Until now, Sol's contribution had previously gone ignored.

Since many site museums in the world have been victims of theft, it was decided not put at risk irreplaceable cultural materials at Cihuatán. Because of this, the Antonio Sol Museum exhibits drawings, photographs, and texts, but no artifacts.

The museum occupies part of the site house which was extensively remodeled and enlarged. It opened its doors to the public on November 17, 2007, with the inauguration of the CIhuatán Archaeological Park.

The Antonio Sol Museum (with a person standing at the entrance) occupies most of the site house, which also has restrooms, an area for personnel and maintenance, and the project lab. The snack bar is to the right.

A walkway in front of the museum.

The museum entrance and a closeup of the sign over its entrance.

The museum has 11 topical exhibits with texts in Spanish and English. To avoid reading problems frequently encountered in exhibits, large fonts have been used without any decorative backgrounds.

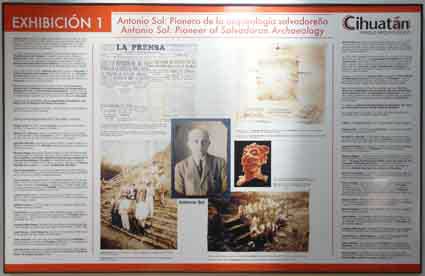

1. Antonio Sol: Pioneer of Salvadoran Archaeology.

2. The Ancient City of Cihuatán (introduction).

3. Mesoamerica: Interlinked Civilizations.

4. Salvadoran Prehistory.

5. Cihuatán's Monumental Center.

6. Cihuatán's Two Ball Courts.

7. Daily Life and Death in the Ancient City.

8. Religion.

9. Trade.

10. Cihuatán's Demise.

11. What is Archaeology?

This example is the first exhibit which describes Antonio Sol's contribution to Cihuatán and Salvadoran archaeology.

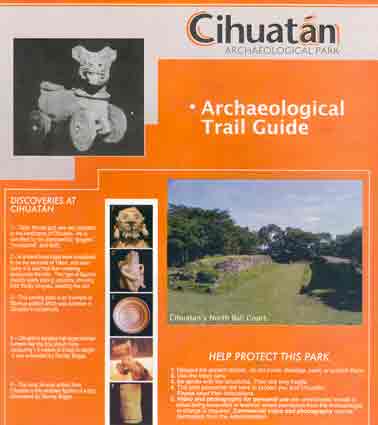

FUNDAR created an archaeological trail at Cihuatán (the term "interpretive trail" is unknown to the majority here). The trail takes the visitor on a self-guided tour through the city's Ceremonial Center, using brochures (in Spanish and English) available at the snack bar. The circuit represents a walk of about 1 kilometer (0.6 mile).

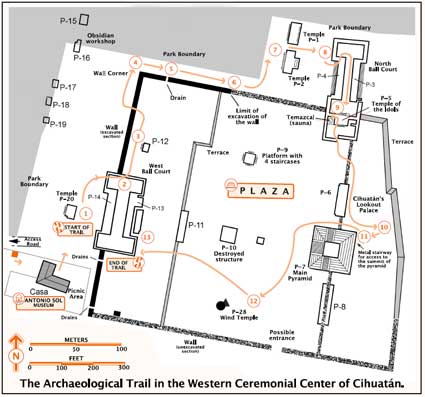

Map showing the route of the archaeological trail.

The cover of the brochure used for the self-guided walk along the archaeological trail (available in Spanish and English). Its graphic design, along with that of the museum exhibits and the park signage, was a donation made by Diego Brito. You can download the brochure by clicking here for the version in English or here for the version in Spanish. Note: these versions are from 2008 and make reference to FUNDAR's participation in the management of other parks.

The trail as it passes along the wall. The trail is marked with whitewashed stones. The stops are indicated by numbered wood posts.

Guazapa Volcano (here framed by a ceiba tree) is a constant companion in your visit to Cihuatán.

The work carried out at Cihuatán by FUNDAR began with a virtually abandoned site.

FUNDAR began improvements at the site in the year 2000, culminating with the inauguration of the Cihuatán Archaeological Park on November 17, 2007. In September, 2009, FUNDAR decided to discontinue its participation in park management in order to fully dedicate itself to investigation and dissemination. In July, 2010, however, FUNDAR and the Secretaría de Cultura signed a new agreement to continue in the co-administration of Cihuatán, and we hope to provide the park with many more improvements.

In the following description, whenever possible we use "before and after" views in order to illustrate the improvements made by FUNDAR with the help of many institutions and individuals.

We began with what was most needed: access. The access road leading to Cihuatán is a kilometer (0.6 miles) long and was impassable for most vehicles. A first task in 2000 was its repair, and now any type of vehicle can reach Cihuatán.

There was no electricity at Cihuatán. Thanks to FUNDAR's actions, in the year 2000 a kilometer of new electric line was installed in order to connect the site house. This photograph was taken the night the lights went on at Cihuatán.

There was no signage at the park. Now there is at the entrance....

...along the long access road...

...and in the new parking area and in other sectors of the park.

FUNDAR implemented the zonification of the park in order to improve its use by visitors. For example, food (and trash) are now limited to the area of the installations. The entrance (left) is regulated, and the exit (right) is by means of a one-way spinning gate.

|

BEFORE Lacking a defined parking area, vehicles entered as far as possible until blocked by the fragile prehispanic buildings. (the temple P-20 is visible next to the bus). |

|

AFTER FUNDAR defined a parking area with capacity for many vehicles in what used to be a "chagüite" (an over-sized mud puddle). |

The Cihuatán House: From Abandonment to a Museum and Workplace

The Cihuatán house was built in the 1970s and was intended for use by projects at the site. It included a space where Archaeologist Stanley Boggs planned to install a site museum, but this never happened.

We found the house in almost total abandonment. Given the absence of park guards, at that time the house was burglarized at will. It was full of sacks (mostly split open) of sherds from excavations all over the country, all covered by a layer of guano from the multitude of bats which had established their quarters in the dilapidated structure. Still more sacks overflowed from a shed originally intended to store lime. These cultural materials had been hurriedly stored here when the old National Museum building was demolished around 1997. Because the site house had been given over to improvised storage, it was impossible to use the building for its intended purpose as a project workspace and museum. It was not even possible to clean the house.

In the year 2000, at FUNDAR's behest, 24-hour guards began their duties to protect the site and the house. In 2005, CONCULTURA authorized the transfer of the materials to one of its storage facilities at another site, for which FUNDAR repackaged over 700 sacks and several boxes.

A small part of the cultural materials which we found piled high in the Cihuatán house.

Left: This man is contemplating approximately 400 sacks crammed into a shed originally intended to store lime for conservation work. Ceramic sherds and obsidian pour from the mostly burst sacks. The sacks included materials from Cara Sucia, Asanyamba (Chapernalito), and several sites now lost under the Cerrón Grande reservoir. Right: We begin repackaging these materials. The shed later served as the basis for building the park's ticket booth and snack bar.

FUNDAR repackaged the materials with some 700 sacks and several boxes in order to transfer them to a CONCULTURA storage facility.

Having finished this first step, of clearing out the house ill-used for storage, FUNDAR began the project of remodeling the house in order to transform it into a site museum, lab, area for personnel and maintenance, and restrooms for visitors. Here are several before and after views of this work:

|

BEFORE The Cihuatán house had a damaged roof, deteriorated floor, deformed metal doors, and many other shortcomings. It was used as an improvised storage area, being packed with cultural materials in deplorable conditions from many different sites, because of which it was impossible to use the house for any other purpose. |

|

AFTER The house after remodeling, with a new roof, new facade (to the right), and new floors, doors, and windows. The rear of the structure was enlarged to build visitor restrooms.

|

|

BEFORE The dilapidated house, with its walkway ("corredor") enclosed with cyclone fence. There was no electricity or water. |

|

AFTER The walkway area after remodeling. It now has decorative wrought iron (hand made), a ceiling made of locally grown reeds ("vara de castilla"), and new doors and windows. There is now electricity and water for gardens and cleaning. |

|

BEFORE The walkway with its deteriorated floor of cement tiles and windows covered with sheet metal. |

|

AFTER The remodeled walkway, with ceramic tile floor, ceiling made of reeds, new wooden doors and windows and decorative wrought iron. |

|

BEFORE The house's main entrance. |

|

AFTER This is now the entrance to the museum. To the right may be seen the restrooms for use by students. A cobblestone path leads around the structure. |

|

BEFORE This area, like the rest of the house, was an improvised store room. |

|

AFTER Now it's a museum where visitors may learn about the prehispanic past. |

|

BEFORE One end of the house before remodeling. At that time there were no restrooms or latrines for visitors to Cihuatán. |

|

AFTER This end of the house was considerably enlarged for the new visitor restrooms. At Cihuatán and two other parks (Joya de Cerén and San Andrés) there are now separate restrooms for regular visitors and for students. This is a singular solution to a local reality: groups of students sometimes trash the park's restrooms, requiring very frequent cleaning and resupply - this proved difficult. The poor conditions of park restrooms were often noted by visitors. Our solution of building separate restrooms for visitors and students has worked. |

|

|

In the past, the lack of water at Cihuatán was a major problem. Thanks to a Ford Motor Company Conservation and Environmental Grant and additional funds from FUNDAR, we built a rainwater capture system. Rain falling on the house's roof is led to a cistern equipped with an electric pump. The water is used for the restrooms, for the landscaping around the house, and to wash cultural materials from excavation. On occasion, when the cistern runs low during the dry season, the Municipality of Aguilares has supplied Cihuatán with "refills" from a water truck (with special thanks to the Mayor, Dr. Wilfredo Peña).

|

|

Left: A sink in one of the modern restrooms built for visitors. Right: For the first time ever, there's water in the house.

|

BEFORE A shed next to the house had originally been built to store lime, but like the house itself, it had been filled with sacks of cultural materials from other sites. It was in poor condition. The upper portion of the walls was crumbling. The roof was made of fragments of "duralita" (a popular cement-based corrugated roofing material). |

|

AFTER FUNDAR used the base of the shed to build a snack bar and (on the other side, with an internal division) the CONCULTURA's ticket booth where visitors pay entrance fees. |

|

|

|

CONCULTURA's ticket booth was built on the other side of the former shed, with a view of the parking area. The people responsible for collecting fees are Gloria Palma Alfaro and Gérman Alexander Reyes Guevara.

Improvements Within the Park: Conservation, Public Access, and Visual Enhancement

|

BEFORE This small temple platform (Structure P-12) was one of several structures excavated in the 1970s but never reburied or consolidated. Most of Cihuatán's architecture consists of stones with earth as a mortar, and after three decades this platform was in poor condition. Trees growing on the structure were another souce of damage. |

|

AFTER Karen Bruhns directed the consolidation of this structure, including some minor restoration (duly indicated in the structure itself) supported by drawings and photographs made by its excavator. It is now a stop along the archeological trail. A bilingual (Spanish/English) monograph on the excavation of this and another structure was published in collaboration between San Francisco State University and FUNDAR with the title,The Excavation of Structures P-12 and P-20 at Cihuatán, El Salvador/ Excavación de las Estructuras P-12 and P20 de Cihuatán, El Salvador, Paper 22, Treganza Anthropology Museum, San Francisco State University (2005). The author was Archaeologist Earl Lubensky, who passed away on May 1st, 2009. |

|

BEFORE Structure P-5 (named the “Temple of the Idols” by Antonio Sol) lies at one end of the North Ball Court. The stairs of this structure were excavated by Sol in 1929, and around 1965 these were partially restored by Tomás Fidias Jiménez. The balustrades (“alfardas”) which frame the stairs originally measured 30 centimeters (12 inches) in height, and what follows above that level (including the “cubes” surmounting the balustrades) was “imaginatively” introduced during that restoration. The stairs were in poor condition because of erosion from the rain and from unrestricted visitor access. |

|

...DURING... Work conducted by FUNDAR under the supervision of Zachary Revene and Pastor Gálvez consolidated the area excavated by Sol, including segments of the terraces on both sides of the stairs. In this photo, Zachary and Pastor are applying a new weather resistant mortar in the interstices between the original stones, without adding other elements. |

|

AFTER Following the consolidation work (which requires periodic monitoring), FUNDAR installed two metal stairways in order to pass over Structure P-5 without damaging it as part of the archaeological trail. Access to the fragile area is limited using green rope on supports of the same color which are nearly invisible during the rainy season. Pending is the removal of the false portions of the balustrades. This conservation work was financed by the Office of Public Affairs

of the US Embassy. |

|

BEFORE The main pyramid (Structure P-7) had a trail cutting up to a meter (3 feet) deep on the corner where visitors used to climb to its top. This damage was progressive, and had gotten to the point where original stones were being displaced. |

|

AFTER FUNDAR built a 21 meter (69 feet) long metal stairway so that visitors can climb the pyramid without damaging it as part of the archaeological trail. The stairway was financed by the Office of Public Affairs of the US Embassy. It was built in three sections in order to facilitate its installation

on the pyramid. If necessary, it can be uninstalled in a single

day. The stairway does not affect the pyramid; it is superficially

supported along the body of the structure, and its base is anchored

in an accumulation of backdirt from Antonio Sol’s 1929 excavation.

|

|

This sign helps guide visitors to the stairway. |

|

BEFORE Despite being one of Cihuatán’s largest structures, until recently the Acropolis was covered by scrub, poorly visible and almost unknown even to archaeologists. The scrub would be burned over every year by vandals in order to gather firewood (from saplings killed by the fire) and to hut animals flushed out by the flames. |

|

...DURING... We cleared the brush and planted grass on the “new” plaza which was exposed by this work. Under FUNDAR, the area planted in grass has increased from about 1 hectare to 5 (2.5 to 12 acres). |

|

AFTER You can now ponder the Acropolis and its plaza in their full splendor. Although the Acropolis is not yet open to visitors, this view is part of the archaeological trail. The Acropolis was the location of Cihuatán’s royal palace. |

|

|

| The maintenance of 5 hectares (12 acres) of lawn requires much work during the rainy season. Left: Antonio Castillo handling a lawn mower. Right: He has the more ecological help of several sheep. | |

And so ends another day at Cihuatán (silhouettes of a ceiba tree and San Salvador Volcano).